Jason Schneider

the Camera Collector

Did Nikon really blow Leitz and Zeiss out of the water in 1950?

Not quite, but they sure made Nikkor lenses world class contenders!

By Jason Schneider

Nikon’s origin story: It all began with “optical weapons” for the navy

By the dawn of the 20th century, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had prioritized the goal of achieving self-sufficiency in critical military materials, especially optical devices. To that end, the IJN established an optical research lab in Tokyo in 1906, and in 1909 set up a repair facility to service, and eventually manufacture “optical weapons” such as field binoculars, camera lenses, and cameras for the Japanese military. By the outbreak of World War I, this modest program became critically important since Japan’s armed forces were then almost entirely dependent on overseas suppliers, chiefly German companies, for optical materials, and all exports were suspended. To address the problem of domestic production of optical glass and optical munitions as the war wound down, navy researchers at the Tsukiji Arsenal south of Tokyo began to produce 7 types of optical glass in melts of up to 300kg, to compensate for the interruption of German imports. And on 25 July 1917 Nippon Kogaku was formed through the consolidation of three smaller optical firms, with an operating capital of 2 million yen, and a total of 200 employees, and was tasked with producing optical equipment for scientific, military, and industrial uses. This fledgling company that was to become Nikon was virtually unknown to domestic or international consumers until after World War II.

Nippon Kogaku, then headed up by Wada Kahei, based most of its early optical engineering projects on proven German designs. Indeed, in 1919 the company hired 8 German engineers and technicians to work for NK, all on 5-year contracts. They arrived in January 1921 and immediately set about introducing German optical designs and manufacturing methods into Nippon Kogaku’s production line, resulting in a development trajectory that paralleled the icons of the German optical industry, Zeiss and Leitz. The new company turned out a wide range of precision optical instruments including telescopes, microscopes, binoculars, military rangefinders, and surveying equipment. When the Great Kanto Earthquake struck on 1 September 1923 levelling large portions of Tokyo, the Japanese Navy Ministry immediately arranged for the reconstruction and reorganization of Nippon Kogaku, even rebuilding its production facility at Oimachi, Tokyo so it could continue its research into improving its manufacture of optical glass and gain consistent control over its “optical parameters,” which had been problematic.

Despite the robust support and financing by the navy, Nippon Kogaku was on the brink of insolvency for much of the 1920s due in part to ship tonnage restrictions imposed by the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 that affected both shipbuilding and military suppliers. On the plus side, since the army and navy research facilities had also been destroyed in the earthquake, many talented military engineers and research projects were assigned to Nippon Kogaku, vastly expanding the breadth of the company’s research capabilities, and paving the way for the company’s ascendent future. Another blessing in disguise came with the decision to severely limit “auxiliary vessel tonnage” at the London Naval Conference in 1930, a serious blow to the Japanese navy that they compensated for by maximizing the fleet’s technological capabilities. The result: more business for Nippon Kogaku and more money for R & D. The company’s expansion throughout the ‘30s was fueled by a combination of the growth in naval construction and its expansion into a more diversified product line that, by 1932, included 75mm, 105mm, 120mm, and 180mm Nikkor photographic lenses. Thus began a process that would spur the future growth of Japan’s entire optical industry. A notable sign of things to come: Seiki Kogaku, the company that eventually become Canon Inc., was founded in 1933, and began selling Japan’s first 35mm rangefinder camera with a focal plane shutter, the Hansa Canon, only three years later in 1936. Its in-body lens mount and possibly its rangefinder were made by Nippon Kogaku and it was fitted with a 50mm f/3.5 Nikkor lens! Later military versions of the Hansa and its successor the Canon S sported the breakthrough prewar 50mm f/2 Nikkor lens!

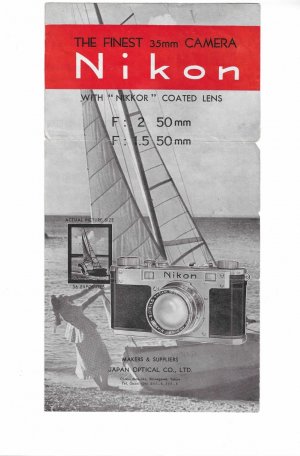

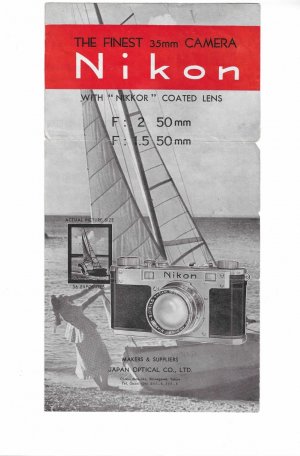

Early English language flyer for Nikon 1 of 1948 showing camera with what may well be the very first postwar 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S.C

Saburo Murakami: The genius designer of 6 classic, vintage Nikkors

(A tip of the lens cap to Kouichi Ohshita whose seminal article NIKKOR – The Thousand and One Nights No.34 is the source of most info below)

Before the war, new Nikkor lenses were designed and formulated at the Optical System Research Department in the Research Division (known as the Ashida Lab), where Saburo Murakami was, in effect, the chief optical designer. At that time, Nippon Kogaku’s main products were rangefinders, periscopes, and binocular telescopes, all intended for military use. But because the Research Division had no manufacturing facilities it had to beg the manufacturing department to give form to every lens design it came up with. The optical designers’ requests were often treated dismissively, and they were derided for “designing lenses just for fun." However, they persisted, devoting all their energies to designing photographic lenses even during the war, and successively developed the 5cm f/1.5 Nikkor (1942), a 7-element, 3-group design based on the 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar of 1932, and various other lenses that would be refined, manufactured, and sold to the public during the postwar period.

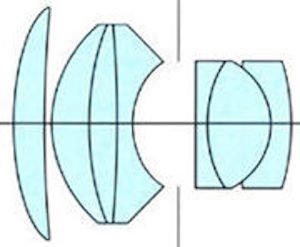

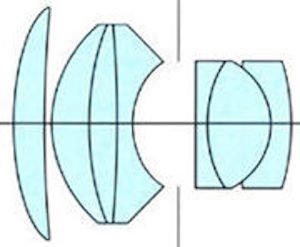

Optical diagram of the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S.C shows its 7-element 3-group construction closely based on 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar of 1932.

At the end of the Second World War in 1945, Nippon Kogaku K.K. ( Nikon Corporation since 1968) was compelled, under U.S. Occupation policies, to reverse course, cease military manufacturing, and switch to designing and turning out consumer goods exclusively. These new products included binoculars and ophthalmic lenses and a series of high quality interchangeable Nikkor lenses for screw mount (LTM) Leica cameras. The new Niikor line included the 5cm f/3.5 (1945), 5cm f/2 (1946), 13.5cm f/4 (1947), 8.5cm f/2 (1948), 3.5cm f/3.5 (1948), and the 5cm f/1.5 (completed in 1949 and put on the market in early 1950). The story has been passed down within Nikon that Saburo Murakami designed all six of these lenses by himself over a 4-year period, a miraculous accomplishment even in today’s computer age, and astonishing at a time when hand-cranked mechanical calculators were all they had.

The reason Nippon Kogaku could pull this off so soon after the war was over is that they had full access to the research data accumulated by Saburo Murakami and others in the Optical System Research Department in the pre-war period. Among the 6 lenses were 3 that had been completed before the war—the 5cm f/3.5 and 5cm f/2 Nikkors that were designed around 1935 for the "Hansa Canon" cameras, and the legendary 5cm f/1.5 Nikkor, the optical design of which was completed in 1942. It’s not known whether the original uncoated 5cm f/1.5 Nikkor was released to the public as a photographic lens at that time, though it's reported to have been put on sale as a specialized lens for X-ray radiography. In any event, the full development and production engineering of the six lenses took a decade or more.

Optical trials and tribulations

Once the relevant data for the three previously mentioned 50mm normal lenses designed by Mr. Murakami were successfully recovered after the war, all were slated for production. However, the raw glass material for the 5cm f/1.5 Nikkor was out of stock and its production had to be postponed until suitable glass became available. However, production of the 5cm f/2 lens Nikkor was successfully resumed because no such obstacle existed, and it became the fastest normal lens for early Nikon cameras. However, within a year of the start of production, Mr. Murakami got the bad news that the stock of glass for the 5cm f/2 Nikkor was also running low. In short, while the distribution of optical glass materials technically resumed after the war, repeated failures occurred, causing the glass stock accumulated during the war to become depleted, thereby constraining the production of certain lenses. Since Nikon continued making its own optical glass during this period (and still does!) some writers have conjectured that the “out of stock” glass referred to above was imported from Schott in Germany. This may indeed be true, but conclusive evidence remains elusive.

If he wanted to keep the 5cm f/2 Nikkor, or any other specific lens, in production at that time, Mr. Murakami had no choice but to change the parameters of some of the glass used to match what was on the “availability check sheet,” recalibrate the design based on the glass in stock, and thus manage to continue the production of the lens. However, within a few months of making these changes, the stock of the remaining glass could again become depleted, and Mr. Murakami would be forced to make additional changes. This confusion finally ended at last in 1948 when reliable full-fledged optical glass distribution resumed. At that point, Mr. Murakami reviewed the design data again, redeveloped the design to deliver more sophisticated performance, and finally brought the 5cm f/2 Nikkor to its perfection.

The six lenses designed by Saburo Murakami constituted the bread-and-butter line in the initial phase of Nikon’s postwar era. The 24 x 32mm format Nikon I, Nikon’s first 35mm rangefinder camera, was successfully developed and offered for sale in Japan in 1948, but the Nikon Legend didn’t really get into full swing internationally until 1956 when the standard 24 x 36mm format Nikon S2 was released. Up to that time, it was largely Murakami’s six Nikkor lenses that kept the camera business afloat. And since the 5cm f/2 Nikkor was at the center of the production of these six lenses, it should be credited as the mainstay that facilitated the post-war rebirth of the camera business before the arrival of the breakthrough 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S (later labeled S.C to denote coating) that arrived in late 1950.

The Canon Connection: Nikkor lenses on Japan’s first rangefinder 35

The very first Canon-branded camera, the Hansa Canon, was initially produced in 1935 and introduced to the Japanese market in February 1936. It used some components of the “Kwanon” of 1933, a Leica-inspired rangefinder 35 prototype made by Seiki-Kogaku-Kenkyusho (Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory), a company founded by Goro Yoshida and Saburo Uchida in that same year. But the Hansa Canon had more advanced features, including its signature spring-loaded pop-up viewfinder, a separate coupled rangefinder, a Contax-style in-body focusing mount (allegedly to get around a Leitz patent for lens-based focusing and rangefinder coupling), a Contax-inspired 3-lobed bayonet lens mount, and a horizontal cloth focal plane shutter with speeds of 1/20-1/500 sec plus Z (for “Zeit” or T) set on a top-mounted rotating dial. The focusing mount was manufactured by Nippon Kogaku (early examples were marked as such) and the standard lens was a collapsible 50mm f/3.5 Nikkor (a high-quality Tessar type) with f/stops from f/3.5 to f/18 in the old continental sequence. A small number of these cameras without the Hansa logo on top were sold directly to professional photographers and the press.

Wartime Canon S cameras with slow speed dials, Imperial Japanese Navy markings. Top camera sports an uncoated 50mm f/2 Nikkor lens.

Since Seiki Kogaku did not produce lenses at the time and Nippon Kogaku did not manufacture cameras, the Hansa Canon was a de facto “marriage of convenience” between two top Japanese companies, Canon and Nikon that were destined to become archrivals. In any event, Nippon Kogaku provided all the lenses for Canon until Canon’s own lens production commenced in 1946-1947. These included the improved “white face” version of the 5cm f/3.5 Nikkor, now with serial numbers, introduced in 1937 and the audacious new 5cm f/2 Nikkor, a 6-element, 3-group Sonnar-type lens that initially had geometric f/stops from f/2 to f/22 set via an internal black ring, and was later offered in a silver finish version with apertures to f/16 set with a conventional external aperture ring. The uncoated 5cm f/2 Nikkor can be found on a small number of Hansa Canon cameras but it’s more common on the later Canon S of 1939 onward, and on wartime military Canon cameras where its extra speed could be put to good use.

Uncoated WWI-era 50mm f/2 Nikkor in Hansa Canon/Canon S bayonet mount was perfected and produced in a coated version after the war.

In October 1939, Precision Optical Industry Co. (Seiki Kogaku) brought forth the Canon S (“Standard”), essentially a Hansa Canon with slow speeds and a Leica-style frame counter below the wind knob, to spur lackluster sales. Production of the Hansa Canon ended in 1940 but production of the Canon S, albeit in limited numbers, continued through World War II. The slow speeds, 1 sec to 1/20 sec, were added on a separate front-mounted dial and included a B setting (confusingly marked Z) and eliminated the T setting. More than 100 5cm f/2 Nikkor lenses were fitted to Canon S cameras during the war, and unlike the 5cm f/3.5 and f/4.5 Nikkors which were constructed entirely of Japanese glass, the 5cm, f/2 Nikkor employed special Schott barium glass imported from Germany, and later tests (the results of which were disputed by Zeiss) found that its performance was superior to the 50mm f/2 Zeiss Sonnar it was based on!

Wartime military Canon S with 50mm f/1.5 Seiko-Kogaku R-Serenar lens. Was it really a rebadged 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor? One expert says yes.

Now here’s where things get interesting. According to Peter Kitchingman’s excellent book, “Canon M39 Rangefinder Lenses 1939-71 – A Collector’s Guide”, between 1942 and 1945 several thousand Canon S bodies were fitted with 5cm f/1.5 lenses marked “Serenar,” the lens name Canon used before adding, and then switching to “Canon Camera Co.”. Kitchingman goes on to say, “The Seiki-Kogaku R-Serenar 5cm f/1.5 lens was probably the first lens that Canon produced in significant numbers between 1943 and 1945. All were originally without diaphragms and used with X-ray cameras during the war, but some were later converted with f/stop diaphragms.” However, in his acclaimed book “Canon Rangefinder Cameras 1933-1968” noted Canon historian Peter Dechert estimates that a total of about 1,600 Canon S cameras, all hand built one at a time by individual craftsmen, were turned out starting in 1938, about 40 per month were being assembled in 1939, none were sold to the public after 1940-41, and only a few hundred—all for the military—were produced in 1943-44, including about 20-100 specially marked cameras going to the Imperial Navy. Are these statements inconsistent. Frankly, I’m not sure, but Dechert is skeptical that Canon (née Seiki Kogaku) a camera company that relied on Nikon (Nippon Kogaku) for its optics since 1935, could suddenly start turning out hundreds, if not thousands, of high-spec 50mm f/1.5 Serenars during WW II. Since Nippon Kogaku had already announced the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor in 1937 and produced it in limited quantities by 1942, Dechert thinks it’s very likely that the wartime Seiki-Kogaku R-Serenar 5cm f/1.5 was really a “badge engineered” 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor. I agree. Oh, there was a 50mm f/1.5 Serenar made by Canon all right, a creditable 7-element, 3-group coated lens based on (what else?) the 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar, but it didn’t arrive until November 1952.

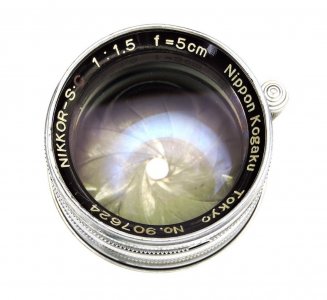

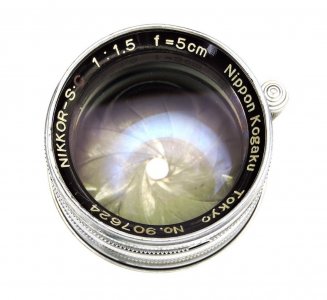

The postwar 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S: Nikons rarest, costliest, normal lens

Introduced in early 1950, the design for the coated 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor was most likely finalized in 1949. They were produced in 2 batches, serial numbers 9052-905520 and 907163-907734, suggesting a total production of about 1100 lenses, though some estimates run as low as 800. The numbers cited above include Nikon S-bayonet and LTM screw mount lenses, the latter much more common in the “905” batch. Even using the 1100-unit figure, the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S is perhaps the least common normal Nikkor—even the rarish 50mm f/3.5 Micro-Nikkors and the 50mm f/1.1’s Nikkors were made in larger numbers! Why so few when fast lenses were the flagships of their respective lines? Because by May 1950, exactly one year after the design of the coated 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor was finalized, Nippon Kogaku had unveiled its blockbuster 50mm f/l.4 Nikkor-S, then the fastest lens in the world! Based on published dates and serial numbers, the 50mm f/l.5 Nikkor-S was available for only one year, and that accounts for its rarity—and its high price among collectors today—typically about $4,500-$6,500, and even higher for mint or very early examples!

Coated postwar 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S.C in Leica screw (LTM) mount, the type that David Douglas Duncan first used to cover the Korean War.

Was the 50mm f/l.4 Nikkor-S or S.C really a better lens? David Douglas Duncan (in his great 1951 book, “This Is War!”) initially stated that he preferred the f/1.5 to the f/1.4 because it was less prone to flare in backlit situations, but then he used the 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C (mostly on his beloved Leicas) exclusively for much of his later (normal lens) work and praised it effusively. The consensus is that both lenses perform about equally well—not too surprising since both are based on the classic 7-element, 3-group 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar formula. Was the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S of 1950 merely a coated version of the limited production prewar/wartime 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor that had been announced in 1937 and produced in limited quantities in 1942 (and perhaps also as the Seiki-Kogaku R-Serenar 5cm f/1.5 in 1943-1945)? Or was the postwar version tweaked or redesigned? It is also said that the fabled 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C was tweaked several times for improved performance over the course of its production (not counting the revised 7-element, 5-group version of 1965, which is an entirely different double Gauss design). Is that true, and if so at what serial numbers did these alleged upgrades occur? Fascinating questions all, but so far, despite intensive research no answers have been forthcoming. If anyone has any additional information on any of this, please reach out to me via RFF.

Postwar Nikkor Lenses: The origin stories

Here are two Nikkor lens stories that have been retold for nearly 75 years and are now firmly established as part of Nikon’s postwar lore. While both are charming and factually accurate, the inferences drawn from them have sometimes been overstated.

Story Number 1

In June, 1950 Jun Miki, a young Japanese photographer, was the first of his nationality to work for Life Magazine, then acclaimed worldwide as the leading visual publication of record. As he was casually snapping some informal “office portraits” of his colleagues, the famed photojournalists David Douglas Duncan and Horace Bristol, with his Leica III, Duncan told him he was wasting his time because the lighting was so poor. But when Miki developed the roll and returned with several 8 x 10 enlargements, Duncan was amazed at the quality of the images. He asked him what lens he was using, which turned out to be a borrowed 85mm f/2 Nikkor made by Nippon Kogaku, a company Duncan had never heard of. Learning that the factory was in nearby Shinagawa he asked for a tour, which Miki arranged. On seeing the quality and attention to detail that went into creating Nikkor lenses and observing a few being tested on the optical bench, Duncan and Bristol concluded that the results were superior to anything they’d previously seen by Leitz or Zeiss, and were so impressed that each left the factory with three new Nikkor lenses, a 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor (the 50mm f/1.4 wasn’t in production yet), an 85mm f/2 Nikkor, a 135mm f/4 Nikkor, all in Leica screw (LTM) mount.

Story Number 2

Barely a week after Miki, Duncan, and Bristol had toured the Nippon Kogaku factory, the Korean War broke out, both Duncan and Bristol were sent to cover it, and they documented the entire war with their newly acquired Nikkor lenses. As was standard practice in those days, they had the film developed locally and sent the negatives back to the home office in New York for selection, editing and publication. Shortly after Duncan’s film was delivered, he received a telegram from the home office asking what he was using since the sharpness was better than anything they’d previously seen. In another instance the lab thought they saw a speck of dust on a negative and, when it wouldn’t wash off as expected, they enlarged it to reveal a helicopter in the distant sky!

When interviewed many years later about his Korean War images and what made them stand out, he replied, “They were brighter and sharper. During the Korean War I carried two Leica IIIc camera bodies loaded with Eastman Super-XX film—one with a Nikkor 50mm f/1.5, then later the 50mm f/1.4; the other with a telephoto, a Nikkor 135mm f/4. I was shooting the stuff in Korea and the guys in New York were asking, ‘What’s going on?’ ‘Oh, he’s got those funny little lenses on his Leica.’ Nobody had ever heard of Nikon. Then some guy from The New York Times wrote a story about it, and that put Nikon on the map.”

Heartwarming stories like these and countless others have conferred an almost mythical status on early postwar Nikkor lenses, and in turn Nikon S- and F-series cameras, that were amplified by many photo writers in the ‘50s and ‘60s. So, what began as heartfelt enthusiasm for the unexpected excellence of Japanese lenses based on hands-on personal experiences has been codified into myth. Herewith some more recent assertions regarding vintage Nikkor lenses of the ‘50s and ‘60s that have appeared in print:

The initial run of postwar Nikkor lenses all hew closely to classic Zeiss optical designs, albeit with some tweaks designed to improve their performance with the available optical glass types. To the best of my knowledge the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor (all versions) is basically a nicely executed, coated offshoot of the 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar of 1932, the vaunted 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C is a modified, ¼-stop faster iteration of the same lens, the 85mm f/2 Nikkor is closely based on the 85mm f/2 Zeiss Sonnar, et cetera. Canon was partial to double Gauss designs, two notable examples being the collapsible 50mm f/1.9 Serenar (later dubbed Canon) and the rigid 50mm f/1.8 Canon, a well-executed 6-element, 4-group Planar design.

The first postwar Nikon and Canon cameras were clearly based on the Contax and Leica respectively, but significantly, each incorporated ingenious technical upgrades not found in its German predecessor. The Nikon I of 1948 (and the Nikon S of 1951) are similar in basic design (but not construction) to the prewar Contax II and postwar Contax IIa, with nearly identical range/viewfinders, in-body focusing helicals, and bayonet lens mounts, but Nikon’s engineers wisely chose to use the more reliable Leica-type rubberized cloth, horizontal travel focal plane shutter in place of the Contax’s pesky vertical metal roller blind shutter. Unlike Zeiss, which never developed more advanced models than the Contax IIa and IIIa of 1950-1961, Nikon upgraded their system with a 1:1 stationary frame line finder, a single stroke wind lever, and standard 24 x 36mm format in the Nikon S2 of 1956 and added true projected parallax-compensating frame lines and other advanced features to compete with the M-series Leicas in the flagship Nikon SP of 1957-1960.

Canon stuck with the Leica screw mount and bottom loading in the landmark Canon IIB of 1949-1951 but added a 3-position combined range/viewfinder that provided different finder magnifications, a minified position that showed the 50mm field, a magnified 1.5x position for more precise focusing, and a 1x position that gave the approximate field of view for 100mm lenses. This brilliant innovation was continued in a succession of models up to the Canon IVSB2 of 1954-1956, widely held to be the finest bottom-loading rangefinder 35 of all time, and in modified form in later hinged-back V- and VI-series Canons, culminating the last of the breed, the Canon 7s and 7sZ of 1967-1968 which had user-selectable parallax-compensating frame lines for 35mm, 50mm 85/100mm and 135mm lenses and built-in CdS meters.

In short, what happened during the post-WWII history of the 35mm rangefinder camera is that by the early ‘50s Nikon, followed by Canon, became serious contenders, challenging the Germans with lenses and cameras that often equaled and sometimes surpassed their German counterparts. Sadly Zeiss, which consistently produced lenses that equaled Nikon’s best, never developed the Contax camera beyond the Contax IIa and IIIa and bowed out by 1961. Leica countered with the sensational Leica M3 in 1954, which (with the M2 and M4) redefined the breed and was conceptually the most advanced 35mm rangefinder of the day, and the 50mm f/2 Summicron, long the best 50mm f/2 in production. The golden age of the interchangeable rangefinder 35 came to an end with the debut of the Nikon F in 1959 and the demise of the Nikon S-series rangefinder cameras shortly thereafter. Today only the timeless analog and digital Leica Ms, with a full complement of breathtakingly expensive M-mount lenses still carry the torch for the full-frame rangefinder system concept.

And what about those previously cited claims made for early postwar Nikkor lenses? Well, the Nikkor lenses David Douglas Duncan used back in the day were certainly designed and constructed to a very high standard and may well have surpassed the Leitz lenses he was using at the time, but it’s doubtful that they were noticeably better than the coated Contax lenses Zeiss was turning out at the time. As far as coatings are concerned, Nippon Kogaku was certainly not unique in turning out coated lenses for military use during the war. Modern interference-based AR coatings were developed by Olexander Smakula, a Ukrainian physicist working for Carl Zeiss Optics, in 1935 and were secretly used on military lenses all through the war. Kodak was coating lenses for military use all through World War II, and it is documented that Leitz made coated versions of their new 50mm f/2 Summitar in 1941 and sent a batch of coated black finished 85mm f/1.5 Summarex lenses to Berlin in 1943 for German government and military use. Is it possible that Nippon Kogaku’s coating was better. Sure, but it’s a hard thing to prove.

Perhaps the most fascinating claim of all is the one about Nippon Kogaku collimating their lenses to achieve perfect focus at 10 feet rather than at infinity (as Zeiss did) to achieve better imaging performance at the most common shooting distances. Collimating (that is, calibrating) a lens to the rangefinder to achieve perfect focus at 10 feet when the images coincide is one thing. Designing a lens so that its optimum object distance is 10 feet is quite another. Since Zeiss and Leitz, and every other optical company has a pretty good idea of how their lenses are used, I remain skeptical about exactly what Nippon Kogaku did or whether it was a decisive coup. But as my physics professor quipped back in the day as he was concluding our section on optics, “When it comes to lenses, we’ve barely begun to scratch the surface!”

Not quite, but they sure made Nikkor lenses world class contenders!

By Jason Schneider

Nikon’s origin story: It all began with “optical weapons” for the navy

By the dawn of the 20th century, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had prioritized the goal of achieving self-sufficiency in critical military materials, especially optical devices. To that end, the IJN established an optical research lab in Tokyo in 1906, and in 1909 set up a repair facility to service, and eventually manufacture “optical weapons” such as field binoculars, camera lenses, and cameras for the Japanese military. By the outbreak of World War I, this modest program became critically important since Japan’s armed forces were then almost entirely dependent on overseas suppliers, chiefly German companies, for optical materials, and all exports were suspended. To address the problem of domestic production of optical glass and optical munitions as the war wound down, navy researchers at the Tsukiji Arsenal south of Tokyo began to produce 7 types of optical glass in melts of up to 300kg, to compensate for the interruption of German imports. And on 25 July 1917 Nippon Kogaku was formed through the consolidation of three smaller optical firms, with an operating capital of 2 million yen, and a total of 200 employees, and was tasked with producing optical equipment for scientific, military, and industrial uses. This fledgling company that was to become Nikon was virtually unknown to domestic or international consumers until after World War II.

Nippon Kogaku, then headed up by Wada Kahei, based most of its early optical engineering projects on proven German designs. Indeed, in 1919 the company hired 8 German engineers and technicians to work for NK, all on 5-year contracts. They arrived in January 1921 and immediately set about introducing German optical designs and manufacturing methods into Nippon Kogaku’s production line, resulting in a development trajectory that paralleled the icons of the German optical industry, Zeiss and Leitz. The new company turned out a wide range of precision optical instruments including telescopes, microscopes, binoculars, military rangefinders, and surveying equipment. When the Great Kanto Earthquake struck on 1 September 1923 levelling large portions of Tokyo, the Japanese Navy Ministry immediately arranged for the reconstruction and reorganization of Nippon Kogaku, even rebuilding its production facility at Oimachi, Tokyo so it could continue its research into improving its manufacture of optical glass and gain consistent control over its “optical parameters,” which had been problematic.

Despite the robust support and financing by the navy, Nippon Kogaku was on the brink of insolvency for much of the 1920s due in part to ship tonnage restrictions imposed by the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 that affected both shipbuilding and military suppliers. On the plus side, since the army and navy research facilities had also been destroyed in the earthquake, many talented military engineers and research projects were assigned to Nippon Kogaku, vastly expanding the breadth of the company’s research capabilities, and paving the way for the company’s ascendent future. Another blessing in disguise came with the decision to severely limit “auxiliary vessel tonnage” at the London Naval Conference in 1930, a serious blow to the Japanese navy that they compensated for by maximizing the fleet’s technological capabilities. The result: more business for Nippon Kogaku and more money for R & D. The company’s expansion throughout the ‘30s was fueled by a combination of the growth in naval construction and its expansion into a more diversified product line that, by 1932, included 75mm, 105mm, 120mm, and 180mm Nikkor photographic lenses. Thus began a process that would spur the future growth of Japan’s entire optical industry. A notable sign of things to come: Seiki Kogaku, the company that eventually become Canon Inc., was founded in 1933, and began selling Japan’s first 35mm rangefinder camera with a focal plane shutter, the Hansa Canon, only three years later in 1936. Its in-body lens mount and possibly its rangefinder were made by Nippon Kogaku and it was fitted with a 50mm f/3.5 Nikkor lens! Later military versions of the Hansa and its successor the Canon S sported the breakthrough prewar 50mm f/2 Nikkor lens!

Early English language flyer for Nikon 1 of 1948 showing camera with what may well be the very first postwar 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S.C

Saburo Murakami: The genius designer of 6 classic, vintage Nikkors

(A tip of the lens cap to Kouichi Ohshita whose seminal article NIKKOR – The Thousand and One Nights No.34 is the source of most info below)

Before the war, new Nikkor lenses were designed and formulated at the Optical System Research Department in the Research Division (known as the Ashida Lab), where Saburo Murakami was, in effect, the chief optical designer. At that time, Nippon Kogaku’s main products were rangefinders, periscopes, and binocular telescopes, all intended for military use. But because the Research Division had no manufacturing facilities it had to beg the manufacturing department to give form to every lens design it came up with. The optical designers’ requests were often treated dismissively, and they were derided for “designing lenses just for fun." However, they persisted, devoting all their energies to designing photographic lenses even during the war, and successively developed the 5cm f/1.5 Nikkor (1942), a 7-element, 3-group design based on the 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar of 1932, and various other lenses that would be refined, manufactured, and sold to the public during the postwar period.

Optical diagram of the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S.C shows its 7-element 3-group construction closely based on 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar of 1932.

At the end of the Second World War in 1945, Nippon Kogaku K.K. ( Nikon Corporation since 1968) was compelled, under U.S. Occupation policies, to reverse course, cease military manufacturing, and switch to designing and turning out consumer goods exclusively. These new products included binoculars and ophthalmic lenses and a series of high quality interchangeable Nikkor lenses for screw mount (LTM) Leica cameras. The new Niikor line included the 5cm f/3.5 (1945), 5cm f/2 (1946), 13.5cm f/4 (1947), 8.5cm f/2 (1948), 3.5cm f/3.5 (1948), and the 5cm f/1.5 (completed in 1949 and put on the market in early 1950). The story has been passed down within Nikon that Saburo Murakami designed all six of these lenses by himself over a 4-year period, a miraculous accomplishment even in today’s computer age, and astonishing at a time when hand-cranked mechanical calculators were all they had.

The reason Nippon Kogaku could pull this off so soon after the war was over is that they had full access to the research data accumulated by Saburo Murakami and others in the Optical System Research Department in the pre-war period. Among the 6 lenses were 3 that had been completed before the war—the 5cm f/3.5 and 5cm f/2 Nikkors that were designed around 1935 for the "Hansa Canon" cameras, and the legendary 5cm f/1.5 Nikkor, the optical design of which was completed in 1942. It’s not known whether the original uncoated 5cm f/1.5 Nikkor was released to the public as a photographic lens at that time, though it's reported to have been put on sale as a specialized lens for X-ray radiography. In any event, the full development and production engineering of the six lenses took a decade or more.

Optical trials and tribulations

Once the relevant data for the three previously mentioned 50mm normal lenses designed by Mr. Murakami were successfully recovered after the war, all were slated for production. However, the raw glass material for the 5cm f/1.5 Nikkor was out of stock and its production had to be postponed until suitable glass became available. However, production of the 5cm f/2 lens Nikkor was successfully resumed because no such obstacle existed, and it became the fastest normal lens for early Nikon cameras. However, within a year of the start of production, Mr. Murakami got the bad news that the stock of glass for the 5cm f/2 Nikkor was also running low. In short, while the distribution of optical glass materials technically resumed after the war, repeated failures occurred, causing the glass stock accumulated during the war to become depleted, thereby constraining the production of certain lenses. Since Nikon continued making its own optical glass during this period (and still does!) some writers have conjectured that the “out of stock” glass referred to above was imported from Schott in Germany. This may indeed be true, but conclusive evidence remains elusive.

If he wanted to keep the 5cm f/2 Nikkor, or any other specific lens, in production at that time, Mr. Murakami had no choice but to change the parameters of some of the glass used to match what was on the “availability check sheet,” recalibrate the design based on the glass in stock, and thus manage to continue the production of the lens. However, within a few months of making these changes, the stock of the remaining glass could again become depleted, and Mr. Murakami would be forced to make additional changes. This confusion finally ended at last in 1948 when reliable full-fledged optical glass distribution resumed. At that point, Mr. Murakami reviewed the design data again, redeveloped the design to deliver more sophisticated performance, and finally brought the 5cm f/2 Nikkor to its perfection.

The six lenses designed by Saburo Murakami constituted the bread-and-butter line in the initial phase of Nikon’s postwar era. The 24 x 32mm format Nikon I, Nikon’s first 35mm rangefinder camera, was successfully developed and offered for sale in Japan in 1948, but the Nikon Legend didn’t really get into full swing internationally until 1956 when the standard 24 x 36mm format Nikon S2 was released. Up to that time, it was largely Murakami’s six Nikkor lenses that kept the camera business afloat. And since the 5cm f/2 Nikkor was at the center of the production of these six lenses, it should be credited as the mainstay that facilitated the post-war rebirth of the camera business before the arrival of the breakthrough 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S (later labeled S.C to denote coating) that arrived in late 1950.

The Canon Connection: Nikkor lenses on Japan’s first rangefinder 35

The very first Canon-branded camera, the Hansa Canon, was initially produced in 1935 and introduced to the Japanese market in February 1936. It used some components of the “Kwanon” of 1933, a Leica-inspired rangefinder 35 prototype made by Seiki-Kogaku-Kenkyusho (Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory), a company founded by Goro Yoshida and Saburo Uchida in that same year. But the Hansa Canon had more advanced features, including its signature spring-loaded pop-up viewfinder, a separate coupled rangefinder, a Contax-style in-body focusing mount (allegedly to get around a Leitz patent for lens-based focusing and rangefinder coupling), a Contax-inspired 3-lobed bayonet lens mount, and a horizontal cloth focal plane shutter with speeds of 1/20-1/500 sec plus Z (for “Zeit” or T) set on a top-mounted rotating dial. The focusing mount was manufactured by Nippon Kogaku (early examples were marked as such) and the standard lens was a collapsible 50mm f/3.5 Nikkor (a high-quality Tessar type) with f/stops from f/3.5 to f/18 in the old continental sequence. A small number of these cameras without the Hansa logo on top were sold directly to professional photographers and the press.

Wartime Canon S cameras with slow speed dials, Imperial Japanese Navy markings. Top camera sports an uncoated 50mm f/2 Nikkor lens.

Since Seiki Kogaku did not produce lenses at the time and Nippon Kogaku did not manufacture cameras, the Hansa Canon was a de facto “marriage of convenience” between two top Japanese companies, Canon and Nikon that were destined to become archrivals. In any event, Nippon Kogaku provided all the lenses for Canon until Canon’s own lens production commenced in 1946-1947. These included the improved “white face” version of the 5cm f/3.5 Nikkor, now with serial numbers, introduced in 1937 and the audacious new 5cm f/2 Nikkor, a 6-element, 3-group Sonnar-type lens that initially had geometric f/stops from f/2 to f/22 set via an internal black ring, and was later offered in a silver finish version with apertures to f/16 set with a conventional external aperture ring. The uncoated 5cm f/2 Nikkor can be found on a small number of Hansa Canon cameras but it’s more common on the later Canon S of 1939 onward, and on wartime military Canon cameras where its extra speed could be put to good use.

Uncoated WWI-era 50mm f/2 Nikkor in Hansa Canon/Canon S bayonet mount was perfected and produced in a coated version after the war.

In October 1939, Precision Optical Industry Co. (Seiki Kogaku) brought forth the Canon S (“Standard”), essentially a Hansa Canon with slow speeds and a Leica-style frame counter below the wind knob, to spur lackluster sales. Production of the Hansa Canon ended in 1940 but production of the Canon S, albeit in limited numbers, continued through World War II. The slow speeds, 1 sec to 1/20 sec, were added on a separate front-mounted dial and included a B setting (confusingly marked Z) and eliminated the T setting. More than 100 5cm f/2 Nikkor lenses were fitted to Canon S cameras during the war, and unlike the 5cm f/3.5 and f/4.5 Nikkors which were constructed entirely of Japanese glass, the 5cm, f/2 Nikkor employed special Schott barium glass imported from Germany, and later tests (the results of which were disputed by Zeiss) found that its performance was superior to the 50mm f/2 Zeiss Sonnar it was based on!

Wartime military Canon S with 50mm f/1.5 Seiko-Kogaku R-Serenar lens. Was it really a rebadged 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor? One expert says yes.

Now here’s where things get interesting. According to Peter Kitchingman’s excellent book, “Canon M39 Rangefinder Lenses 1939-71 – A Collector’s Guide”, between 1942 and 1945 several thousand Canon S bodies were fitted with 5cm f/1.5 lenses marked “Serenar,” the lens name Canon used before adding, and then switching to “Canon Camera Co.”. Kitchingman goes on to say, “The Seiki-Kogaku R-Serenar 5cm f/1.5 lens was probably the first lens that Canon produced in significant numbers between 1943 and 1945. All were originally without diaphragms and used with X-ray cameras during the war, but some were later converted with f/stop diaphragms.” However, in his acclaimed book “Canon Rangefinder Cameras 1933-1968” noted Canon historian Peter Dechert estimates that a total of about 1,600 Canon S cameras, all hand built one at a time by individual craftsmen, were turned out starting in 1938, about 40 per month were being assembled in 1939, none were sold to the public after 1940-41, and only a few hundred—all for the military—were produced in 1943-44, including about 20-100 specially marked cameras going to the Imperial Navy. Are these statements inconsistent. Frankly, I’m not sure, but Dechert is skeptical that Canon (née Seiki Kogaku) a camera company that relied on Nikon (Nippon Kogaku) for its optics since 1935, could suddenly start turning out hundreds, if not thousands, of high-spec 50mm f/1.5 Serenars during WW II. Since Nippon Kogaku had already announced the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor in 1937 and produced it in limited quantities by 1942, Dechert thinks it’s very likely that the wartime Seiki-Kogaku R-Serenar 5cm f/1.5 was really a “badge engineered” 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor. I agree. Oh, there was a 50mm f/1.5 Serenar made by Canon all right, a creditable 7-element, 3-group coated lens based on (what else?) the 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar, but it didn’t arrive until November 1952.

The postwar 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S: Nikons rarest, costliest, normal lens

Introduced in early 1950, the design for the coated 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor was most likely finalized in 1949. They were produced in 2 batches, serial numbers 9052-905520 and 907163-907734, suggesting a total production of about 1100 lenses, though some estimates run as low as 800. The numbers cited above include Nikon S-bayonet and LTM screw mount lenses, the latter much more common in the “905” batch. Even using the 1100-unit figure, the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S is perhaps the least common normal Nikkor—even the rarish 50mm f/3.5 Micro-Nikkors and the 50mm f/1.1’s Nikkors were made in larger numbers! Why so few when fast lenses were the flagships of their respective lines? Because by May 1950, exactly one year after the design of the coated 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor was finalized, Nippon Kogaku had unveiled its blockbuster 50mm f/l.4 Nikkor-S, then the fastest lens in the world! Based on published dates and serial numbers, the 50mm f/l.5 Nikkor-S was available for only one year, and that accounts for its rarity—and its high price among collectors today—typically about $4,500-$6,500, and even higher for mint or very early examples!

Coated postwar 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S.C in Leica screw (LTM) mount, the type that David Douglas Duncan first used to cover the Korean War.

Was the 50mm f/l.4 Nikkor-S or S.C really a better lens? David Douglas Duncan (in his great 1951 book, “This Is War!”) initially stated that he preferred the f/1.5 to the f/1.4 because it was less prone to flare in backlit situations, but then he used the 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C (mostly on his beloved Leicas) exclusively for much of his later (normal lens) work and praised it effusively. The consensus is that both lenses perform about equally well—not too surprising since both are based on the classic 7-element, 3-group 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar formula. Was the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor-S of 1950 merely a coated version of the limited production prewar/wartime 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor that had been announced in 1937 and produced in limited quantities in 1942 (and perhaps also as the Seiki-Kogaku R-Serenar 5cm f/1.5 in 1943-1945)? Or was the postwar version tweaked or redesigned? It is also said that the fabled 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C was tweaked several times for improved performance over the course of its production (not counting the revised 7-element, 5-group version of 1965, which is an entirely different double Gauss design). Is that true, and if so at what serial numbers did these alleged upgrades occur? Fascinating questions all, but so far, despite intensive research no answers have been forthcoming. If anyone has any additional information on any of this, please reach out to me via RFF.

Postwar Nikkor Lenses: The origin stories

Here are two Nikkor lens stories that have been retold for nearly 75 years and are now firmly established as part of Nikon’s postwar lore. While both are charming and factually accurate, the inferences drawn from them have sometimes been overstated.

Story Number 1

In June, 1950 Jun Miki, a young Japanese photographer, was the first of his nationality to work for Life Magazine, then acclaimed worldwide as the leading visual publication of record. As he was casually snapping some informal “office portraits” of his colleagues, the famed photojournalists David Douglas Duncan and Horace Bristol, with his Leica III, Duncan told him he was wasting his time because the lighting was so poor. But when Miki developed the roll and returned with several 8 x 10 enlargements, Duncan was amazed at the quality of the images. He asked him what lens he was using, which turned out to be a borrowed 85mm f/2 Nikkor made by Nippon Kogaku, a company Duncan had never heard of. Learning that the factory was in nearby Shinagawa he asked for a tour, which Miki arranged. On seeing the quality and attention to detail that went into creating Nikkor lenses and observing a few being tested on the optical bench, Duncan and Bristol concluded that the results were superior to anything they’d previously seen by Leitz or Zeiss, and were so impressed that each left the factory with three new Nikkor lenses, a 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor (the 50mm f/1.4 wasn’t in production yet), an 85mm f/2 Nikkor, a 135mm f/4 Nikkor, all in Leica screw (LTM) mount.

Story Number 2

Barely a week after Miki, Duncan, and Bristol had toured the Nippon Kogaku factory, the Korean War broke out, both Duncan and Bristol were sent to cover it, and they documented the entire war with their newly acquired Nikkor lenses. As was standard practice in those days, they had the film developed locally and sent the negatives back to the home office in New York for selection, editing and publication. Shortly after Duncan’s film was delivered, he received a telegram from the home office asking what he was using since the sharpness was better than anything they’d previously seen. In another instance the lab thought they saw a speck of dust on a negative and, when it wouldn’t wash off as expected, they enlarged it to reveal a helicopter in the distant sky!

When interviewed many years later about his Korean War images and what made them stand out, he replied, “They were brighter and sharper. During the Korean War I carried two Leica IIIc camera bodies loaded with Eastman Super-XX film—one with a Nikkor 50mm f/1.5, then later the 50mm f/1.4; the other with a telephoto, a Nikkor 135mm f/4. I was shooting the stuff in Korea and the guys in New York were asking, ‘What’s going on?’ ‘Oh, he’s got those funny little lenses on his Leica.’ Nobody had ever heard of Nikon. Then some guy from The New York Times wrote a story about it, and that put Nikon on the map.”

Heartwarming stories like these and countless others have conferred an almost mythical status on early postwar Nikkor lenses, and in turn Nikon S- and F-series cameras, that were amplified by many photo writers in the ‘50s and ‘60s. So, what began as heartfelt enthusiasm for the unexpected excellence of Japanese lenses based on hands-on personal experiences has been codified into myth. Herewith some more recent assertions regarding vintage Nikkor lenses of the ‘50s and ‘60s that have appeared in print:

- Nippon Kogaku imposed extreme quality control standards in its lens manufacturing processes that surpassed those employed by Leitz and Zeiss in Germany at the time. These included 100% inspection of each element, testing each assembled lens to ensure that only the best lenses left the factory, and tighter tolerances to ensure greater consistency and minimize lens-to-lens variation.

- Nippon Kogaku’s hard coating process, perfected over the course of coating lenses for the military during WWII, was far superior, at least in the immediate postwar period, to that of Leitz and Zeiss, neither of which coated their lenses during the war. The result: until the launch of the 50mm f/2 Leitz Summicron in 1953, Nikon rangefinder lenses had better color performance, less flare, and increased sharpness thanks to their superior coating.

- Nippon Kogaku collimated their lenses to achieve perfect focus at 10 feet (rather than at infinity as Zeiss did) to achieve better imaging performance at the most common shooting distances.

The initial run of postwar Nikkor lenses all hew closely to classic Zeiss optical designs, albeit with some tweaks designed to improve their performance with the available optical glass types. To the best of my knowledge the 50mm f/1.5 Nikkor (all versions) is basically a nicely executed, coated offshoot of the 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar of 1932, the vaunted 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C is a modified, ¼-stop faster iteration of the same lens, the 85mm f/2 Nikkor is closely based on the 85mm f/2 Zeiss Sonnar, et cetera. Canon was partial to double Gauss designs, two notable examples being the collapsible 50mm f/1.9 Serenar (later dubbed Canon) and the rigid 50mm f/1.8 Canon, a well-executed 6-element, 4-group Planar design.

The first postwar Nikon and Canon cameras were clearly based on the Contax and Leica respectively, but significantly, each incorporated ingenious technical upgrades not found in its German predecessor. The Nikon I of 1948 (and the Nikon S of 1951) are similar in basic design (but not construction) to the prewar Contax II and postwar Contax IIa, with nearly identical range/viewfinders, in-body focusing helicals, and bayonet lens mounts, but Nikon’s engineers wisely chose to use the more reliable Leica-type rubberized cloth, horizontal travel focal plane shutter in place of the Contax’s pesky vertical metal roller blind shutter. Unlike Zeiss, which never developed more advanced models than the Contax IIa and IIIa of 1950-1961, Nikon upgraded their system with a 1:1 stationary frame line finder, a single stroke wind lever, and standard 24 x 36mm format in the Nikon S2 of 1956 and added true projected parallax-compensating frame lines and other advanced features to compete with the M-series Leicas in the flagship Nikon SP of 1957-1960.

Canon stuck with the Leica screw mount and bottom loading in the landmark Canon IIB of 1949-1951 but added a 3-position combined range/viewfinder that provided different finder magnifications, a minified position that showed the 50mm field, a magnified 1.5x position for more precise focusing, and a 1x position that gave the approximate field of view for 100mm lenses. This brilliant innovation was continued in a succession of models up to the Canon IVSB2 of 1954-1956, widely held to be the finest bottom-loading rangefinder 35 of all time, and in modified form in later hinged-back V- and VI-series Canons, culminating the last of the breed, the Canon 7s and 7sZ of 1967-1968 which had user-selectable parallax-compensating frame lines for 35mm, 50mm 85/100mm and 135mm lenses and built-in CdS meters.

In short, what happened during the post-WWII history of the 35mm rangefinder camera is that by the early ‘50s Nikon, followed by Canon, became serious contenders, challenging the Germans with lenses and cameras that often equaled and sometimes surpassed their German counterparts. Sadly Zeiss, which consistently produced lenses that equaled Nikon’s best, never developed the Contax camera beyond the Contax IIa and IIIa and bowed out by 1961. Leica countered with the sensational Leica M3 in 1954, which (with the M2 and M4) redefined the breed and was conceptually the most advanced 35mm rangefinder of the day, and the 50mm f/2 Summicron, long the best 50mm f/2 in production. The golden age of the interchangeable rangefinder 35 came to an end with the debut of the Nikon F in 1959 and the demise of the Nikon S-series rangefinder cameras shortly thereafter. Today only the timeless analog and digital Leica Ms, with a full complement of breathtakingly expensive M-mount lenses still carry the torch for the full-frame rangefinder system concept.

And what about those previously cited claims made for early postwar Nikkor lenses? Well, the Nikkor lenses David Douglas Duncan used back in the day were certainly designed and constructed to a very high standard and may well have surpassed the Leitz lenses he was using at the time, but it’s doubtful that they were noticeably better than the coated Contax lenses Zeiss was turning out at the time. As far as coatings are concerned, Nippon Kogaku was certainly not unique in turning out coated lenses for military use during the war. Modern interference-based AR coatings were developed by Olexander Smakula, a Ukrainian physicist working for Carl Zeiss Optics, in 1935 and were secretly used on military lenses all through the war. Kodak was coating lenses for military use all through World War II, and it is documented that Leitz made coated versions of their new 50mm f/2 Summitar in 1941 and sent a batch of coated black finished 85mm f/1.5 Summarex lenses to Berlin in 1943 for German government and military use. Is it possible that Nippon Kogaku’s coating was better. Sure, but it’s a hard thing to prove.

Perhaps the most fascinating claim of all is the one about Nippon Kogaku collimating their lenses to achieve perfect focus at 10 feet rather than at infinity (as Zeiss did) to achieve better imaging performance at the most common shooting distances. Collimating (that is, calibrating) a lens to the rangefinder to achieve perfect focus at 10 feet when the images coincide is one thing. Designing a lens so that its optimum object distance is 10 feet is quite another. Since Zeiss and Leitz, and every other optical company has a pretty good idea of how their lenses are used, I remain skeptical about exactly what Nippon Kogaku did or whether it was a decisive coup. But as my physics professor quipped back in the day as he was concluding our section on optics, “When it comes to lenses, we’ve barely begun to scratch the surface!”

Last edited:

KoNickon

Nick Merritt

Great piece, Jason. It would have been interesting to get ahold of DDD's actual lenses and test them against their CZJ and Leitz competition. It wouldn't surprise me if the Nippon Kogaku factory pulled out particularly choice samples for him to buy, knowing that his endorsement would be most helpful for their sales. But I also wouldn't be surprised if they were able to exercise a higher degree of quality control than Zeiss (for instance) could at that time. Interesting stuff, all the same.

Here's a question though, and the answer may be obvious to some, but not me: Though the Japanese makers were working off of German designs at that time, are there lens designs of Japanese origin of the same status as the Zeiss and Leica classics? Or have the contributions of the Japanese makers been more of an incremental (though important) nature -- improved coatings, new glass types, zoom designs?

Here's a question though, and the answer may be obvious to some, but not me: Though the Japanese makers were working off of German designs at that time, are there lens designs of Japanese origin of the same status as the Zeiss and Leica classics? Or have the contributions of the Japanese makers been more of an incremental (though important) nature -- improved coatings, new glass types, zoom designs?

Jason Schneider

the Camera Collector

Thanks for your kind words. Assuming that DDD was then using Leitz lenses on his Leica, I'm sure that the new Nikkors could have given him an edge because Leitz didn't set the standard for high speed normal lenses until the 50mm f/2 Summicron of 1953 and the second (non-ASPH) version of the 50mm f/1.4 Summilux in 1961. By the mid 1960s and later all the leading Japanese lens makers (Nikon,Canon, Pentax, Topcon et al) were creating innovative lenses, especially zooms, that equaled or surpassed traditional German designs, and today Japan turns out some of the best lenses in the world.

das

Well-known

Great read once again!

My two cents and this may be an unpopular opinion: I don't think that Nikon's 50mm f/2 or 1.4 were really anything special. Yes, they were fast and yes there was the close focus feature. However, they are still focus-shifty Sonnar derivatives with questionable bokeh and just "ok" coatings for color photography. They were also mass produced lenses, being bundled with virtually every Tower/Nicca camera sold at Sears. Nikon may have had slightly better coatings than the Leitz lenses of the 50s. They definitely appear to be "harder" to damage.

Where Nikon really outshined Leica initially was the production of a bunch of FLs that were not 50. The 35mm f/2.5 (and 1.8), the 105mm f/2.5, the 28mm, and 25mm were part of a much better overall lens lineup than what Leitz was producing up until the first generation of redesigned M lenses. Canon also had an equally great lens lineup by 1956 or so. Even Nikon's swansong 1964 Olympic Nikkor 50mm f/1.4 was prob the equal of the Gen 1 & 2 Summilux and with no focus shift. The 2000 version is certainly very special.

To me, and as you described, what often sets 1950s lenses apart were their coatings. I think that Konica's amber coating probably was the best of all major manufacturers - like on the II and III RFs, the later Pearls, the Koniflex, and the M39 lenses (50/1.9, 50/3.5). Konica also used Voigtlander designs that did not focus shift. Leitz's coatings got phenomenally better during the late 1950s, but even those can't hold a candle to today's lenses.

My two cents and this may be an unpopular opinion: I don't think that Nikon's 50mm f/2 or 1.4 were really anything special. Yes, they were fast and yes there was the close focus feature. However, they are still focus-shifty Sonnar derivatives with questionable bokeh and just "ok" coatings for color photography. They were also mass produced lenses, being bundled with virtually every Tower/Nicca camera sold at Sears. Nikon may have had slightly better coatings than the Leitz lenses of the 50s. They definitely appear to be "harder" to damage.

Where Nikon really outshined Leica initially was the production of a bunch of FLs that were not 50. The 35mm f/2.5 (and 1.8), the 105mm f/2.5, the 28mm, and 25mm were part of a much better overall lens lineup than what Leitz was producing up until the first generation of redesigned M lenses. Canon also had an equally great lens lineup by 1956 or so. Even Nikon's swansong 1964 Olympic Nikkor 50mm f/1.4 was prob the equal of the Gen 1 & 2 Summilux and with no focus shift. The 2000 version is certainly very special.

To me, and as you described, what often sets 1950s lenses apart were their coatings. I think that Konica's amber coating probably was the best of all major manufacturers - like on the II and III RFs, the later Pearls, the Koniflex, and the M39 lenses (50/1.9, 50/3.5). Konica also used Voigtlander designs that did not focus shift. Leitz's coatings got phenomenally better during the late 1950s, but even those can't hold a candle to today's lenses.

Curious what is prompting the inclusion of this comment? Not criticizing, just wondering what relevance?They were also mass produced lenses, being bundled with virtually every Tower/Nicca camera sold at Sears.

A lens is inspected at Tokyo's Nikon camera plant, on January 5, 1952. #

AP Photo/Bob Schutz

das

Well-known

it always seems to me that the relative cost of a lens when offered new on the market is usually a pretty good indicator of its quality/performance. I think that the f/1.4 and f/2 Nikkor lenses could be analogized to a "standard 50mm f/1.8" that came with every SLR. While standard (bundled) lenses can be very good, SLR manufacturers offered lower-volume 1.4s and 1.2s at much higher price points for the pros. For instance, Nikon had the f/1.1 lens as its marquee 50mm. Later Canon RFs had the 50mm f/1.8 as their standard bundled lens, a capable but not remarkable lens. But Canon also offered better, faster, and more expensive 50s.Curious what is prompting the inclusion of this comment? Not criticizing, just wondering what relevance?

A lens is inspected at Tokyo's Nikon camera plant, on January 5, 1952. #

AP Photo/Bob Schutz

Rob-F

Likes Leicas

Excellent treatment of this era of optical history! Thank you, Jason.

pgk

Well-known

Which if any any photographic lenses have suddenly produced a step change when they came out?

wlewisiii

Just another hotel clerk

Not sure what you mean by a "step change".

But the ones that radically changed photography? In alpha order stolen from Wiki:

Angenieux retrofocus

Cooke triplet

Double-Gauss

Goerz Dagor

Leitz Elmar

Rapid Rectilinear

Zeiss Sonnar

Zeiss Planar

Zeiss Tessar

Arguably the two most important are the Rapid Rectilinear and the Tessar. But both were eclipsed by the far more important development of anti-reflection coatings by Zeiss shortly before WWII. Their red T made the rest almost irrelevant leaving us with mostly double-gauss based lenses.

But the ones that radically changed photography? In alpha order stolen from Wiki:

Angenieux retrofocus

Cooke triplet

Double-Gauss

Goerz Dagor

Leitz Elmar

Rapid Rectilinear

Zeiss Sonnar

Zeiss Planar

Zeiss Tessar

Arguably the two most important are the Rapid Rectilinear and the Tessar. But both were eclipsed by the far more important development of anti-reflection coatings by Zeiss shortly before WWII. Their red T made the rest almost irrelevant leaving us with mostly double-gauss based lenses.

pgk

Well-known

Interesting list. The Rapid Rectilinear was attributed to Dallmeyer who patented it but actually Thomas Grubb (of Dubin) produced Doublets which seem to also fit Kingslake's description of the RR prior to the Dallmeyer patent. The patented form of Dallmeyer's lens still had to undergo modification until it became the RR as we think of it too, so it was more of a evolved lens than a sudden step change. I'm not so familiar with the Tessar story to comment. Many of the lenses listed probably only came about because of the new glass types produced in Jena in the 1890s which arguable also had a substantial effect on photographic lens possibilities. Alongside increasing demand at the time too. The invention of the Cooke Triplet is said to have been somewhat influenced by Sir Howard Grubb (Thomas's son) who apparently had Dennis Taylor look at how it might be possible to improve telescope doublets. It was after this that Taylor decided that a better solution was a triplet .....

wes loder

Photographer/Historian

According to the story told by Duncan and Bristol, they randomly chose lens off the production line.

wes loder

Photographer/Historian

Excellent write up, Jason. For readers looking for more information, I recommend my book on Nikon in this period. "The Nikon Camera in America, 1946-1953." McFarland Press and still in print.

Jason Schneider

the Camera Collector

Hi Wes, Thanks so much for your kind words. Unfortunately I don't have a copy of your book, but I did look through a copy a while back and it is excellent. Glad to hear it's still in print! Cheers, Jason

Jason Schneider

the Camera Collector

Fascinating! I never dug into the origins of the Rapid Rectilinear that deeply, but some of the most gorgeously rendered pictures I ever shot were taken on an old 3A Folding Kodak with a B&L Rapid Rectilinear at f/16. The 3-1/4 x 5-1/2-inch Postcard Format was magnificent--it's a shame Verichrome Pan 122 was discontinued in 1970, and cutting sheet film to size is too much of a hassle.Interesting list. The Rapid Rectilinear was attributed to Dallmeyer who patented it but actually Thomas Grubb (of Dubin) produced Doublets which seem to also fit Kingslake's description of the RR prior to the Dallmeyer patent. The patented form of Dallmeyer's lens still had to undergo modification until it became the RR as we think of it too, so it was more of a evolved lens than a sudden step change. I'm not so familiar with the Tessar story to comment. Many of the lenses listed probably only came about because of the new glass types produced in Jena in the 1890s which arguable also had a substantial effect on photographic lens possibilities. Alongside increasing demand at the time too. The invention of the Cooke Triplet is said to have been somewhat influenced by Sir Howard Grubb (Thomas's son) who apparently had Dennis Taylor look at how it might be possible to improve telescope doublets. It was after this that Taylor decided that a better solution was a triplet .....

Last edited:

Jason Schneider

the Camera Collector

I like your list, but IMHO the Elmar is really a Tessar even though Max Berek claimed he arrived at the formula by modifying his 5-element Leitz Anastigmat/Elmax and placed its iris diaphragm behind the front element instead of in the middle.Not sure what you mean by a "step change".

But the ones that radically changed photography? In alpha order stolen from Wiki:

Angenieux retrofocus

Cooke triplet

Double-Gauss

Goerz Dagor

Leitz Elmar

Rapid Rectilinear

Zeiss Sonnar

Zeiss Planar

Zeiss Tessar

Arguably the two most important are the Rapid Rectilinear and the Tessar. But both were eclipsed by the far more important development of anti-reflection coatings by Zeiss shortly before WWII. Their red T made the rest almost irrelevant leaving us with mostly double-gauss based lenses.

Last edited:

pgk

Well-known

In the 1860s photgraphers were much like they are today, discussing, arguing about and judging equipment. They did so via photographic journals much like magazines and now forms. And they got equally heated. I've been researching the Grubbs as I have a collection of their lenses, and there is surprisingly acrimonious correspondence between the lens makers of the day in the press. And just as today the manufacturers vie for postion as producers of the best equipment with supporters and detractors, the same happened then, and often surprisingly quickly. Such histories are complicated though with some bits missing when copies of the journals are difficult to find.Fascinating! I never dug into the origins of the Rapid Rectilinear that deeply, but some of the most gorgeously rendered pictures I ever shot were taken on an old 3A Folding Kodak with a B&L Rapid Rectilinear at f/16. The 3-1/4 x 5-1/2-inch Postcard Format was magnificent--it's a shame Verichrome Pan 122 was discontinued in 1970, and cutting sheet oil to size is too much of a hassle.

And very occasionally it is possible to find out that a particular and still existant photograph was taken with a specific lens. For example Samuel Bourne climbed up into the Himalayas in 1866, to the Manirung Pass and photographed the pass itself using a “Grubb C lens, fifteen inches focus, and smallest stop” (his photo reference is 1468). The pass is at 18,600 feet and at the time this was the highest altitude at which photographs had been take, he climbed up into the Himalayas, to the Manirung Pass and photographed the pass itself using a “Grubb C lens, fifteen inches focus, and smallest stop” (his photo reference is 1468). The pass is at 18,600 feet and at the time this was the highest altitude at which photographs had been taken. Copies of this wet plate photograph still exist and so it is one of a few for which we have the 'exif' data.

pixie79

Member

It wasn't only the lenses. More contrasty! It was the Nikon-F and Pentax cameras. We all voted with our wallets!

Reading this article makes me realize how much I miss Popular Photography where each month I looked for Jason's section before looking at anything else.

The coatings, especially the inner coatings, of the 1940s Nikkor lenses are better than the Leica and Zeiss lenses of the same period. I picked up a collapsible Nikkor 5cm F2 that was like Wax paper on a Nicca III for "cheap". Ten Minutes to open up and clean the inner haze, coatings were perfect. On a Leica lens- haze gets into the coating, same with the inner coatings of the Zeiss lenses made during the war. The coating often comes off with the haze.

Zeiss coated most of the 5cm Sonnars from 1939 and on, including those made during the war. The Biogon 3.5cm F2.8 was also coated. The 13.5cm F4 Sonnar - probably the last to be coated, those from the wartime years I've seen were not coated.

My Nikkor-SC 5cm F1.5 is a few lenses away from DDD's lens, same batch, very close SN. Same with my 13.5cm F4 Nikkor. The focus was perfect used wide-open on my M9 from day 1. As per a Museum collection of DDD, he had lens 905203. I have 905189.

I've shot the Nikkor 5cm F1.5 side-by-side with the Summarit 5cm F1.5 with perfect glass. The Nikkor is optimized for F1.5, the Summarit is optimized for F2.8 or so used close-up. The actual focul length of the Five Summarits that I have disassembled are all marked 51.1 internally. This accounts for focus shift. Focus is perfect at infinity at F1.5, but front-focuses at minimum focus. Stopping down to F2.8 effectively increases focal length, meaning best for close-up work stopped down. I modified two Summarits to have a longer focal length by putting a spacer to move the rear groups out. Turns out a J-8 shim works perfectly.

The first "tweek" that I've seen with the early production Nikkor-SC 5cm F1.4 occurred sometime early in the "NKJ" lenses. I have a 5005 series lens and a very early NKJ lens that have the same optics. I tried using a part from a 33xxxx 5cm F1.4 lens, note that the diameter of the optics and fixture had changed by ~1mm.

Next few weeks are very busy for me- After that, will have some time to compare these lenses. In particular, comparing the 5cm F1.5 with the early 5cm F1.4- looking for flare will be an interesting test. And comparing the Nikkor-SC 5cm F1.5 with the first-batch 1932 CZJ 5cm F1.5 is a must, along with the 1934 Sonnar- which is reformulated.

I have compared my early Nikkor 5cm F2 with the Canon Serenar 5cm F2, glass on both is perfect. This lens was not in production for long, was a single-helical design with rotating front. The diameter of the front element is much bigger than the Summar, but has the same 1-2-2-1 layout that Canon used for their 50/1.9, 50/1.8, and 50/1.4 lenses. The Black Canon 50/1.8 is reformulated from the chrome lens, and is probably the sharpest Canon 50mm lens made. Or how you end up with Eleven Different Canon 50mm lenses. Collect them all. Prices are much less than Nikkor lenses, unless you want a 50/0.95 these days. Prices are up from $200 when RFF was new. We just cannot keep a secret.

Jason- thankyou for the fascinating article.

The coatings, especially the inner coatings, of the 1940s Nikkor lenses are better than the Leica and Zeiss lenses of the same period. I picked up a collapsible Nikkor 5cm F2 that was like Wax paper on a Nicca III for "cheap". Ten Minutes to open up and clean the inner haze, coatings were perfect. On a Leica lens- haze gets into the coating, same with the inner coatings of the Zeiss lenses made during the war. The coating often comes off with the haze.

Zeiss coated most of the 5cm Sonnars from 1939 and on, including those made during the war. The Biogon 3.5cm F2.8 was also coated. The 13.5cm F4 Sonnar - probably the last to be coated, those from the wartime years I've seen were not coated.

My Nikkor-SC 5cm F1.5 is a few lenses away from DDD's lens, same batch, very close SN. Same with my 13.5cm F4 Nikkor. The focus was perfect used wide-open on my M9 from day 1. As per a Museum collection of DDD, he had lens 905203. I have 905189.

I've shot the Nikkor 5cm F1.5 side-by-side with the Summarit 5cm F1.5 with perfect glass. The Nikkor is optimized for F1.5, the Summarit is optimized for F2.8 or so used close-up. The actual focul length of the Five Summarits that I have disassembled are all marked 51.1 internally. This accounts for focus shift. Focus is perfect at infinity at F1.5, but front-focuses at minimum focus. Stopping down to F2.8 effectively increases focal length, meaning best for close-up work stopped down. I modified two Summarits to have a longer focal length by putting a spacer to move the rear groups out. Turns out a J-8 shim works perfectly.

The first "tweek" that I've seen with the early production Nikkor-SC 5cm F1.4 occurred sometime early in the "NKJ" lenses. I have a 5005 series lens and a very early NKJ lens that have the same optics. I tried using a part from a 33xxxx 5cm F1.4 lens, note that the diameter of the optics and fixture had changed by ~1mm.

Next few weeks are very busy for me- After that, will have some time to compare these lenses. In particular, comparing the 5cm F1.5 with the early 5cm F1.4- looking for flare will be an interesting test. And comparing the Nikkor-SC 5cm F1.5 with the first-batch 1932 CZJ 5cm F1.5 is a must, along with the 1934 Sonnar- which is reformulated.

I have compared my early Nikkor 5cm F2 with the Canon Serenar 5cm F2, glass on both is perfect. This lens was not in production for long, was a single-helical design with rotating front. The diameter of the front element is much bigger than the Summar, but has the same 1-2-2-1 layout that Canon used for their 50/1.9, 50/1.8, and 50/1.4 lenses. The Black Canon 50/1.8 is reformulated from the chrome lens, and is probably the sharpest Canon 50mm lens made. Or how you end up with Eleven Different Canon 50mm lenses. Collect them all. Prices are much less than Nikkor lenses, unless you want a 50/0.95 these days. Prices are up from $200 when RFF was new. We just cannot keep a secret.

Jason- thankyou for the fascinating article.

Last edited:

wlewisiii

Just another hotel clerk

Thank you as well, Brian.

I currently have a Nikon 50/2 and a Canon 50/1.4 (both with a classic UV filter and modern hood) I've had both chrome & black Canon 50/1.8's in the past (and I just know I will again in the future ) but I'm hard pressed to see that they were sharper - all are exquisite lenses for my uses.

) but I'm hard pressed to see that they were sharper - all are exquisite lenses for my uses.

The real ringer in the bunch of my classics is the other one you turned me on to - my Chiyoko Super Rokkor 50/2. THAT is an utterly amazing lens that is nearly unknown and goes for far less than it should.

I currently have a Nikon 50/2 and a Canon 50/1.4 (both with a classic UV filter and modern hood) I've had both chrome & black Canon 50/1.8's in the past (and I just know I will again in the future

The real ringer in the bunch of my classics is the other one you turned me on to - my Chiyoko Super Rokkor 50/2. THAT is an utterly amazing lens that is nearly unknown and goes for far less than it should.

Two 5cm F1.5 lenses available in the Late 1940s for the Leica.

and

One is the Nikkor 5cm F1.5, wide-open and the other is my Clean Glass Leitz Xenon that has been cleaned of haze. The Xenon is uncoated, but has a beautiful bloom. Mine is from the last batch.

As if anyone needs to ask- Nikkor is the top one.

and

One is the Nikkor 5cm F1.5, wide-open and the other is my Clean Glass Leitz Xenon that has been cleaned of haze. The Xenon is uncoated, but has a beautiful bloom. Mine is from the last batch.

As if anyone needs to ask- Nikkor is the top one.

Last edited:

Share:

-

This site uses cookies to help personalise content, tailor your experience and to keep you logged in if you register.

By continuing to use this site, you are consenting to our use of cookies.