Jason Schneider

the Camera Collector

An American Classic 35: The Mercury by Universal Camera Corp.

Challenging German supremacy with ingenuity and oddball innovation

By Jason Schneider

At the depth of the Great Depression in 1933, the taxi business was in terrible shape—not many folks wanted to hire a cab when they weren’t sure where their next meal was coming from and couldn’t make their mortgage payments. Perhaps that’s why two entrepreneurial guys with financial connections to the taxicab industry decided to start a new camera company that eventually became Universal Camera Corp of New York. Otto Githens was an executive for a loan company that financed taxicab operations and his unlikely partner was Jacob Shapiro, an agent for a taxicab insurance underwriter. Neither of them had one iota of experience in the camera business, but they had a dream—to undercut the likes Eastman Kodak and Ansco in the photographic mass market by producing and selling a camera for a mere 39 cents, a price everyone could afford.

In analyzing Kodak’s business model, the partners realized that the real money was not in selling cameras, but in selling film and processing, a recurring expense that would ensure a reliable revenue stream. So, they contracted with film manufacturer Gevaert of Belgium to produce 6-exposure roll film in a special size (Univex No. 00) that would only fit their camera, which they offered at 10 cents per roll! The final step was to set up processing labs across the U.S. to develop and print the non-standard film, thus ensuring control of the entire supply chain.

The Univex A, a simple plastic point and shoot, was a roaring success, but did Universal Camera Corp. steal the design for its first product? It's possible.

Their cockamamie plan was a roaring success and the fledging company sold 2.6 million Univex Model A cameras in 1934 along with millions of rolls of film, which they also processed. The dark side: It’s been widely reported that Universal pirated the design for the Univex A, a rudimentary plastic compact box camera with a fold-up wire frame finder, from Norton Labs of New York, the company that had designed it at the behest of (you guessed it) Universal. Norton was supposed to have supplied it to them as a subcontractor and had even made the molding dies. Norton did go on to produce and successfully sell its own version if the Univex A, and the company was eventually acquired by Universal, resulting in (what else?) the Norton-Univex variant.

A tip of the lens cap to Cynthia A. Repinski for researching and writing a book that tells the whole story of the Universal Camera Corp. and its weird products.

Telling the complete checkered history of the Universal Camera Company and its plethora of unique, innovative, brilliant, and, at times, “crappy,” products would take a sizeable (272-page!) book. That volume, The Univex Story by Cynthia A. Repinski, Centennial Photo Service, 1991, is still available from the printer or online at about $30 per copy. Universal made everything from simple point and shoots to 8mm movie cameras to 35mm scale focusing and rangefinder cameras, to folding roll film cameras, to twin lens reflexes, to enlargers, projectors, and even radios. But perhaps the company’s wisest decision was hiring George Kende as Chief Design Engineer in 1935. Kende was a brilliant and innovative engineer who had a remarkable facility for creating sophisticated designs for cameras and photographic equipment that provided advanced features yet could be produced at moderate cost by unskilled or semi-skilled labor. His crowning achievements were Universal Camera Corp.’s Mercury I and Mercury II, both half-frame 35s with rotary shutters that were among the few American-made cameras to successfully challenge European dominance in the immediate pre-war and post-WWII

eras.

Rare Mercury I (Model CC-1500 ) of 1939 with world's fastest top shutter speed of 1/1500, 35mm f/2.7 Universal Tricor lens, and Univex extinction meter in its accessory shoe. Like all Mercury CC models it took standard double-perf 35mm film wound on special spools.

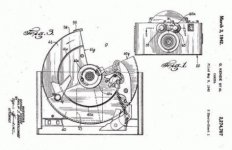

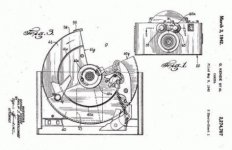

Patent application for Mercury II rotary shutter mechanism dated 1942. It operated on the same principle as the Mercury I shutter with minor detail differences.

The Mercury I, officially dubbed the Model CC, debuted in 1938, and its design is a tribute to George Kende’s out-of-the-box thinking and engineering brilliance. The centerpiece of the design is a full rotary sector focal plane shutter derived from those used in Univex 8mm movie cameras that had been introduced in 1936. The shutter consists of 2 interconnected round metal discs with its central pivot point positioned just above the top edge of the 35mm film. By varying the pie-sliced opening between the two discs that pass in front of the film to make the exposure, timed shutter speeds of 1/20-1/1000 sec (plus B and T) were obtainable. The shutter used simple modular components which were easy to assemble and only a single spindle was required rather than up to 4 spindles used in conventional focal plane shutters. Because the opening and closing blades were rigidly geared together and driven by a single spring there is no “fading,” uneven exposures due to variations in first and second curtain speeds. And since the disk traveled though half a rotation before the exposure was made it acted as flywheel to stabilize it speed, resulting in more uniform exposures. Indeed, tests conducted at the Harvard Observatory indicated that the Mercury I’s shutter was more accurate than those in the Contax and the Leica, quite an achievement for an upstart American company that produced cheap cameras for the masses.

The whole enchilada: Mercury I with non-coupled rangefinder and extinction meter on top, Univex Rapid Winder, and rare 35mm f/2 Hexar Anastigmat lens.

Closeup of Mercury I with 35mm f/2 Hexar lens. Lens was made by Wollensak and its name suggests it was a 6-element design, but no diagram has emerged.

The major downside to the shutters in all Mercury cameras is that the full disk rotary shutter does not fit the form factor of a conventional 35mm camera—it requires a “hump” along the back plane to accommodate the large circular blades. Also, this shutter system can only cover the (vertical) half frame (18 x 24mm) format. A full frame (24 x 36 mm) version of the Mercury would require building a camera the size of an 800-pound gorilla. Still, the camera is small, and light compared to others in its class, measuring 5-1/4 x 3-3.8 x 1-3/8 inches (W x H x D) and weighing in at 18.7 ounces, and (like the Leica) its rounded ends enhance its impression of sleekness. Because of the shutter design, the film wind and shutter speed setting knobs had to be on the front of the camera, but Universal turned that to their advantage, touting the benefits of having a “control center” on the front of the camera.

Mercury I ad of 1939 shows selling price of camera listed as $25. Note reference to model new CC-1500 and 35mm f/2 Hexar lens in copy.

For the record, the Mercury CC (retrospectively called the Mercury I) launched in 1938 was constructed of unfinished aluminum alloy castings covered in leather, has a small somewhat squinty Galilean optical finder with parallax adjustment markings, a recessed shutter release on top, and it used proprietary Univex #200 film, 65 exposures of standard 35mm film wound on special spools to fit the camera. The Mercury I was also the world’s first camera to incorporate a hot shoe, a flash contact (for F sync bulbs) built into the accessory shoe! Available lenses included the 35mm f/2.7 Tricor and 35mm f/3.5 Tricor (both triplets) and the 35mm f/2 Hexar Anastigmat (most often found on the rare model CC-1500 with 1/1500 sec top shutter speed introduced in 1939). These cameras depended on modular design and simplified construction to enable them to be assembled largely with unskilled labor, and they lacked such refinements as a coupled rangefinder, slow shutter speeds and built-in light meters which were becoming popular by the late ‘30s. Universal rose to the challenge by building two side by side accessory shoes into the top of the camera and offering clip-on “system” accessories including an extinction type light meter and an uncoupled rangefinder.

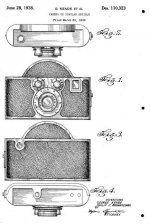

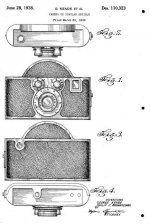

Original 1938 patent drawing the Mercury 1 by George Kende, surely one of the most innovative and brilliant camera designers America has produced.

The designers also took advantage of the front-mounted wind lever to design an accessory vertical rapid wind lever that could be operated like a trigger with the right middle finger while the pressing the shutter release with the index finger, achieving one frame per sec or even faster! Note: Early versions of the Mercury had a plain leather covering on the rear of the shutter disc extension atop the camera; later versions replaced the leather with an additional depth of field chart covering f/2.0 and f/2.7 lenses, to supplement the DOF chart on the front that begins at f/3.5. All but the earliest Mercurys also provide a film movement indicator (it looks like a slotted screw) on the bottom. Whatever you may think of the idiosyncratic styling of the Mercury I or II they sure looks like “serious” cameras, and that was the point.

One of the Mercury I’s biggest selling points was, of course, its top shutter speed of 1/1000 sec, unusual for a camera in its moderate price class—it sold for a paltry $25 in 1938 while German-made cameras from Leitz and Zeiss were selling for hundreds of dollars. However, the Contax II and III boasted a top shutter speed of 1/1250 sec and that rankled the patriotic Americans of Universal Camera Corp. As a result, management tasked the engineering department with devising a faster version of the Mercury’s rotary shutter in a bid to capture the coveted title of “fastest” (still) camera in the world”. Since the camera’s rotary shutter turns at a more-or-less constant speed, the best way of achieving a faster shutter speed is to narrow the angle of the pie-shaped slit that scans the film. However, this would have entailed a redesign of the shutter, a costly and time-consuming procedure, so they were ordered to simply increase the spring tension, causing the shutter discs to run faster at all shutter speeds. The new top shutter speed was 1/1500, the fastest in the world, the shutter speed knob was suitably reconfigured, and the back plate of the “hump” was marked “Model CC-1500.” What Chief Engineer George Kende thought of this has not come down to us, but he must have been disgusted with what he knew to be a “cheap and dirty” solution to producing a higher-speed shutter that seriously impaired its long-term reliability. The CC-1500 was afflicted with springs that break, become fatigued, or lose their temper and it’s unusual to find a fully functional example today.

Rare very clean Mercury CC-1500 with top shutter speed of 1/1500 sec with 35mm f/2.7 Tricor lens and extinction meter. Auction asking price: $299.95.

The only good news is for collectors. The CC-1500 now qualifies as a rare find— indeed as only an estimated 3,000 were manufactured, all in 1939, compared to approximately 45,000 of the standard Mercury Model CC. With a Wollensak-made 35mm f/3.5 Tricor lens, the CC-1500 sold new in 1939 for $29.75. The camera was also available with the Wollensak-made 35mm f/2.0 Hexar Anastigmat lens, a rare option that more than doubled the price of the outfit to a breathtaking $65! Contrary to some speculation, the 35mm f/2 Hexar was not vaporware—it was a real product, not a mere catalog listing, and they occasionally show up in auction listings. There were supposedly 75mm and 125mm telephoto lenses offered as well but I haven’t found one yet so please let me know if you run across one. Today you can occasionally snag a nice CC-1500 for a few hundred bucks but some go for crazy prices. As a user-collectible you’re much better off with a standard CC (aka Mercury I) or better yet a Mercury II (Model CX) that takes standard 35mm cartridges.

Mercury II debuted in 1945. Biggest change: it takes standard 35mm cartridges, requiring a larger body but it also has larger film wind and shutter speed dials, and a rewind control and knob. Its aluminum/magnesium body castings tend to oxidize, giving it a funky appearance, but this is the one to shoot with.

Like many U.S. companies, Universal Camera Corp. ceased normal operations during WWII and switched to producing items for the armed forces. So, instead of turning out cameras they manufactured Universal branded binoculars, which are said to be well made and of good quality. By the time Universal resumed camera production in 1945 they had decided to reconfigure the popular Mercury I or CC to accept standard 35mm cartridges. New aluminum/magnesium die castings were required and as a result the Mercury II (officially called the CX) was ¼-inch taller and wider than the Mercury I (CC). The new Mercury II (CX) measures 5.71 x 3.74 x 2.36 inches (W x H x D) and it weighs in at 21.2 ounces—substantially larger and noticeably heavier than the Mercury I but still relatively compact.

Magazine ad 1948 for Universal cameras shows Mercury II sold at a discount price of $54.40 with 35mm f/2.7 Tricor, considerably less than the Fair Trade list price, of $82.

In other respects, the new model, which was widely advertised as “The Camera for Color,” had the same general specs as the original: a rotary metal focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/20-1/1000 sec, plus T and B, F sync via the hot shoe, and a squinty Galilean optical finder with parallax compensation markings. It does have a redesigned film counter dial, larger wind and shutter speed knobs, a synthetic textured covering in place of leather, and no neck strap lugs like its predecessor. It took the same array of screw mount lenses cited above, and its aluminum/magnesium alloy body castings tend to oxidize and become funky, unlike the aluminum bodied Mercury I, which retains its shine.

The Mercury II (model CX) camera was produced all through the ‘40s and into the ‘50s—it was offered at the discount price of $54.40 with 35mm f/2.7 Tricor lens in 1948.

Mercury II back view shows DOF scale (top) film reminder dial (left) and exposure calculator (center). Note oxidation on metal parts.

Open hinged back of Mercury II shows rewind knob and film chamber for standard 35mm cartridges, take-up spool, and rotary shutter in closed position.

Universal Camera Corp. became insolvent in 1952, but somehow managed to soldier on until 1964. Today you can snag a clean Mercury II with 35mm f/2.7 or f/3.5 Tricor lens for about $60-$100 at online auction sites, but any Mercury camera (model I, II or CC-1500) with the coveted 35mm f/2.0 Hexar will fetch upwards of a few hundred bucks. In general, Mercury cameras are reliable, fun to shoot with and a great way to amaze your friends. They can all take sharp pictures, but re- rolling 35mm film to fit a Mercury I will only appeal to fanatics and masochists, and lots of luck getting a broken Mercury repaired. Still, they’re something only those crazy Americans could’ve come up with, and that accounts for much of their enduring charm.

Challenging German supremacy with ingenuity and oddball innovation

By Jason Schneider

At the depth of the Great Depression in 1933, the taxi business was in terrible shape—not many folks wanted to hire a cab when they weren’t sure where their next meal was coming from and couldn’t make their mortgage payments. Perhaps that’s why two entrepreneurial guys with financial connections to the taxicab industry decided to start a new camera company that eventually became Universal Camera Corp of New York. Otto Githens was an executive for a loan company that financed taxicab operations and his unlikely partner was Jacob Shapiro, an agent for a taxicab insurance underwriter. Neither of them had one iota of experience in the camera business, but they had a dream—to undercut the likes Eastman Kodak and Ansco in the photographic mass market by producing and selling a camera for a mere 39 cents, a price everyone could afford.

In analyzing Kodak’s business model, the partners realized that the real money was not in selling cameras, but in selling film and processing, a recurring expense that would ensure a reliable revenue stream. So, they contracted with film manufacturer Gevaert of Belgium to produce 6-exposure roll film in a special size (Univex No. 00) that would only fit their camera, which they offered at 10 cents per roll! The final step was to set up processing labs across the U.S. to develop and print the non-standard film, thus ensuring control of the entire supply chain.

The Univex A, a simple plastic point and shoot, was a roaring success, but did Universal Camera Corp. steal the design for its first product? It's possible.

Their cockamamie plan was a roaring success and the fledging company sold 2.6 million Univex Model A cameras in 1934 along with millions of rolls of film, which they also processed. The dark side: It’s been widely reported that Universal pirated the design for the Univex A, a rudimentary plastic compact box camera with a fold-up wire frame finder, from Norton Labs of New York, the company that had designed it at the behest of (you guessed it) Universal. Norton was supposed to have supplied it to them as a subcontractor and had even made the molding dies. Norton did go on to produce and successfully sell its own version if the Univex A, and the company was eventually acquired by Universal, resulting in (what else?) the Norton-Univex variant.

A tip of the lens cap to Cynthia A. Repinski for researching and writing a book that tells the whole story of the Universal Camera Corp. and its weird products.

Telling the complete checkered history of the Universal Camera Company and its plethora of unique, innovative, brilliant, and, at times, “crappy,” products would take a sizeable (272-page!) book. That volume, The Univex Story by Cynthia A. Repinski, Centennial Photo Service, 1991, is still available from the printer or online at about $30 per copy. Universal made everything from simple point and shoots to 8mm movie cameras to 35mm scale focusing and rangefinder cameras, to folding roll film cameras, to twin lens reflexes, to enlargers, projectors, and even radios. But perhaps the company’s wisest decision was hiring George Kende as Chief Design Engineer in 1935. Kende was a brilliant and innovative engineer who had a remarkable facility for creating sophisticated designs for cameras and photographic equipment that provided advanced features yet could be produced at moderate cost by unskilled or semi-skilled labor. His crowning achievements were Universal Camera Corp.’s Mercury I and Mercury II, both half-frame 35s with rotary shutters that were among the few American-made cameras to successfully challenge European dominance in the immediate pre-war and post-WWII

eras.

Rare Mercury I (Model CC-1500 ) of 1939 with world's fastest top shutter speed of 1/1500, 35mm f/2.7 Universal Tricor lens, and Univex extinction meter in its accessory shoe. Like all Mercury CC models it took standard double-perf 35mm film wound on special spools.

Patent application for Mercury II rotary shutter mechanism dated 1942. It operated on the same principle as the Mercury I shutter with minor detail differences.

The Mercury I, officially dubbed the Model CC, debuted in 1938, and its design is a tribute to George Kende’s out-of-the-box thinking and engineering brilliance. The centerpiece of the design is a full rotary sector focal plane shutter derived from those used in Univex 8mm movie cameras that had been introduced in 1936. The shutter consists of 2 interconnected round metal discs with its central pivot point positioned just above the top edge of the 35mm film. By varying the pie-sliced opening between the two discs that pass in front of the film to make the exposure, timed shutter speeds of 1/20-1/1000 sec (plus B and T) were obtainable. The shutter used simple modular components which were easy to assemble and only a single spindle was required rather than up to 4 spindles used in conventional focal plane shutters. Because the opening and closing blades were rigidly geared together and driven by a single spring there is no “fading,” uneven exposures due to variations in first and second curtain speeds. And since the disk traveled though half a rotation before the exposure was made it acted as flywheel to stabilize it speed, resulting in more uniform exposures. Indeed, tests conducted at the Harvard Observatory indicated that the Mercury I’s shutter was more accurate than those in the Contax and the Leica, quite an achievement for an upstart American company that produced cheap cameras for the masses.

The whole enchilada: Mercury I with non-coupled rangefinder and extinction meter on top, Univex Rapid Winder, and rare 35mm f/2 Hexar Anastigmat lens.

Closeup of Mercury I with 35mm f/2 Hexar lens. Lens was made by Wollensak and its name suggests it was a 6-element design, but no diagram has emerged.

The major downside to the shutters in all Mercury cameras is that the full disk rotary shutter does not fit the form factor of a conventional 35mm camera—it requires a “hump” along the back plane to accommodate the large circular blades. Also, this shutter system can only cover the (vertical) half frame (18 x 24mm) format. A full frame (24 x 36 mm) version of the Mercury would require building a camera the size of an 800-pound gorilla. Still, the camera is small, and light compared to others in its class, measuring 5-1/4 x 3-3.8 x 1-3/8 inches (W x H x D) and weighing in at 18.7 ounces, and (like the Leica) its rounded ends enhance its impression of sleekness. Because of the shutter design, the film wind and shutter speed setting knobs had to be on the front of the camera, but Universal turned that to their advantage, touting the benefits of having a “control center” on the front of the camera.

Mercury I ad of 1939 shows selling price of camera listed as $25. Note reference to model new CC-1500 and 35mm f/2 Hexar lens in copy.

For the record, the Mercury CC (retrospectively called the Mercury I) launched in 1938 was constructed of unfinished aluminum alloy castings covered in leather, has a small somewhat squinty Galilean optical finder with parallax adjustment markings, a recessed shutter release on top, and it used proprietary Univex #200 film, 65 exposures of standard 35mm film wound on special spools to fit the camera. The Mercury I was also the world’s first camera to incorporate a hot shoe, a flash contact (for F sync bulbs) built into the accessory shoe! Available lenses included the 35mm f/2.7 Tricor and 35mm f/3.5 Tricor (both triplets) and the 35mm f/2 Hexar Anastigmat (most often found on the rare model CC-1500 with 1/1500 sec top shutter speed introduced in 1939). These cameras depended on modular design and simplified construction to enable them to be assembled largely with unskilled labor, and they lacked such refinements as a coupled rangefinder, slow shutter speeds and built-in light meters which were becoming popular by the late ‘30s. Universal rose to the challenge by building two side by side accessory shoes into the top of the camera and offering clip-on “system” accessories including an extinction type light meter and an uncoupled rangefinder.

Original 1938 patent drawing the Mercury 1 by George Kende, surely one of the most innovative and brilliant camera designers America has produced.

The designers also took advantage of the front-mounted wind lever to design an accessory vertical rapid wind lever that could be operated like a trigger with the right middle finger while the pressing the shutter release with the index finger, achieving one frame per sec or even faster! Note: Early versions of the Mercury had a plain leather covering on the rear of the shutter disc extension atop the camera; later versions replaced the leather with an additional depth of field chart covering f/2.0 and f/2.7 lenses, to supplement the DOF chart on the front that begins at f/3.5. All but the earliest Mercurys also provide a film movement indicator (it looks like a slotted screw) on the bottom. Whatever you may think of the idiosyncratic styling of the Mercury I or II they sure looks like “serious” cameras, and that was the point.

One of the Mercury I’s biggest selling points was, of course, its top shutter speed of 1/1000 sec, unusual for a camera in its moderate price class—it sold for a paltry $25 in 1938 while German-made cameras from Leitz and Zeiss were selling for hundreds of dollars. However, the Contax II and III boasted a top shutter speed of 1/1250 sec and that rankled the patriotic Americans of Universal Camera Corp. As a result, management tasked the engineering department with devising a faster version of the Mercury’s rotary shutter in a bid to capture the coveted title of “fastest” (still) camera in the world”. Since the camera’s rotary shutter turns at a more-or-less constant speed, the best way of achieving a faster shutter speed is to narrow the angle of the pie-shaped slit that scans the film. However, this would have entailed a redesign of the shutter, a costly and time-consuming procedure, so they were ordered to simply increase the spring tension, causing the shutter discs to run faster at all shutter speeds. The new top shutter speed was 1/1500, the fastest in the world, the shutter speed knob was suitably reconfigured, and the back plate of the “hump” was marked “Model CC-1500.” What Chief Engineer George Kende thought of this has not come down to us, but he must have been disgusted with what he knew to be a “cheap and dirty” solution to producing a higher-speed shutter that seriously impaired its long-term reliability. The CC-1500 was afflicted with springs that break, become fatigued, or lose their temper and it’s unusual to find a fully functional example today.

Rare very clean Mercury CC-1500 with top shutter speed of 1/1500 sec with 35mm f/2.7 Tricor lens and extinction meter. Auction asking price: $299.95.

The only good news is for collectors. The CC-1500 now qualifies as a rare find— indeed as only an estimated 3,000 were manufactured, all in 1939, compared to approximately 45,000 of the standard Mercury Model CC. With a Wollensak-made 35mm f/3.5 Tricor lens, the CC-1500 sold new in 1939 for $29.75. The camera was also available with the Wollensak-made 35mm f/2.0 Hexar Anastigmat lens, a rare option that more than doubled the price of the outfit to a breathtaking $65! Contrary to some speculation, the 35mm f/2 Hexar was not vaporware—it was a real product, not a mere catalog listing, and they occasionally show up in auction listings. There were supposedly 75mm and 125mm telephoto lenses offered as well but I haven’t found one yet so please let me know if you run across one. Today you can occasionally snag a nice CC-1500 for a few hundred bucks but some go for crazy prices. As a user-collectible you’re much better off with a standard CC (aka Mercury I) or better yet a Mercury II (Model CX) that takes standard 35mm cartridges.

Mercury II debuted in 1945. Biggest change: it takes standard 35mm cartridges, requiring a larger body but it also has larger film wind and shutter speed dials, and a rewind control and knob. Its aluminum/magnesium body castings tend to oxidize, giving it a funky appearance, but this is the one to shoot with.

Like many U.S. companies, Universal Camera Corp. ceased normal operations during WWII and switched to producing items for the armed forces. So, instead of turning out cameras they manufactured Universal branded binoculars, which are said to be well made and of good quality. By the time Universal resumed camera production in 1945 they had decided to reconfigure the popular Mercury I or CC to accept standard 35mm cartridges. New aluminum/magnesium die castings were required and as a result the Mercury II (officially called the CX) was ¼-inch taller and wider than the Mercury I (CC). The new Mercury II (CX) measures 5.71 x 3.74 x 2.36 inches (W x H x D) and it weighs in at 21.2 ounces—substantially larger and noticeably heavier than the Mercury I but still relatively compact.

Magazine ad 1948 for Universal cameras shows Mercury II sold at a discount price of $54.40 with 35mm f/2.7 Tricor, considerably less than the Fair Trade list price, of $82.

In other respects, the new model, which was widely advertised as “The Camera for Color,” had the same general specs as the original: a rotary metal focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/20-1/1000 sec, plus T and B, F sync via the hot shoe, and a squinty Galilean optical finder with parallax compensation markings. It does have a redesigned film counter dial, larger wind and shutter speed knobs, a synthetic textured covering in place of leather, and no neck strap lugs like its predecessor. It took the same array of screw mount lenses cited above, and its aluminum/magnesium alloy body castings tend to oxidize and become funky, unlike the aluminum bodied Mercury I, which retains its shine.

The Mercury II (model CX) camera was produced all through the ‘40s and into the ‘50s—it was offered at the discount price of $54.40 with 35mm f/2.7 Tricor lens in 1948.

Mercury II back view shows DOF scale (top) film reminder dial (left) and exposure calculator (center). Note oxidation on metal parts.

Open hinged back of Mercury II shows rewind knob and film chamber for standard 35mm cartridges, take-up spool, and rotary shutter in closed position.

Universal Camera Corp. became insolvent in 1952, but somehow managed to soldier on until 1964. Today you can snag a clean Mercury II with 35mm f/2.7 or f/3.5 Tricor lens for about $60-$100 at online auction sites, but any Mercury camera (model I, II or CC-1500) with the coveted 35mm f/2.0 Hexar will fetch upwards of a few hundred bucks. In general, Mercury cameras are reliable, fun to shoot with and a great way to amaze your friends. They can all take sharp pictures, but re- rolling 35mm film to fit a Mercury I will only appeal to fanatics and masochists, and lots of luck getting a broken Mercury repaired. Still, they’re something only those crazy Americans could’ve come up with, and that accounts for much of their enduring charm.

neal3k

Well-known

Thanks for a great narrative about the Mercury half-frame camera. You have inspired me.

I have one on the shelf that I inherited many years ago and kept because I collect and shoot old cameras (I have your three books from the old magazine days.) Until today, I have never thought much about mine, a Mercury II with the 2.7 lens. I tested it after reading your article and found the shutter was sluggish and the f/stop and focus rings were stuck but otherwise, it seems pretty decent. I've exercised the shutter about 50 times and it seems to be getting smoother. I've also tried to free the grease without disassembling the f/stop and focus rings and will work on it more tomorrow. I can always shoot at f/2.7 at 15 feet but that will be a bit limiting. It won't stop me from some test shots though, even if I don't fix it.

I have one on the shelf that I inherited many years ago and kept because I collect and shoot old cameras (I have your three books from the old magazine days.) Until today, I have never thought much about mine, a Mercury II with the 2.7 lens. I tested it after reading your article and found the shutter was sluggish and the f/stop and focus rings were stuck but otherwise, it seems pretty decent. I've exercised the shutter about 50 times and it seems to be getting smoother. I've also tried to free the grease without disassembling the f/stop and focus rings and will work on it more tomorrow. I can always shoot at f/2.7 at 15 feet but that will be a bit limiting. It won't stop me from some test shots though, even if I don't fix it.

The Mercury II has some interesting features:

1) Takes standard 35mm film

2) Unique oddball design American made half frame,

especially mounting the outlandishly odd accessory rangefinder.

3) Probably the lowest priced interchangeable lens half frame in today's marketplace

4) What lens adapters are possible? M lenses or only SLR ?

5) Shutter may be adaptable as a cheese grater or lawn mower

1) Takes standard 35mm film

2) Unique oddball design American made half frame,

especially mounting the outlandishly odd accessory rangefinder.

3) Probably the lowest priced interchangeable lens half frame in today's marketplace

4) What lens adapters are possible? M lenses or only SLR ?

5) Shutter may be adaptable as a cheese grater or lawn mower

zuiko85

Mentor

This is off topic but…it would be nice to see an article about Spiratone, certainly a part of photography history for many of us old timers.

Mr_Flibble

In Tabulas Argenteas Refero

A light polishing with ceramic stove top cleaner seems to do wonders to bring out the shine again.

Though the design makes it hard to reach all nooks and crannies.

Though the design makes it hard to reach all nooks and crannies.

shawn

Mentor

Thanks for a great narrative about the Mercury half-frame camera. You have inspired me.

I have one on the shelf that I inherited many years ago and kept because I collect and shoot old cameras (I have your three books from the old magazine days.) Until today, I have never thought much about mine, a Mercury II with the 2.7 lens. I tested it after reading your article and found the shutter was sluggish and the f/stop and focus rings were stuck but otherwise, it seems pretty decent. I've exercised the shutter about 50 times and it seems to be getting smoother. I've also tried to free the grease without disassembling the f/stop and focus rings and will work on it more tomorrow. I can always shoot at f/2.7 at 15 feet but that will be a bit limiting. It won't stop me from some test shots though, even if I don't fix it.

You can unscrew the lens and then remove the cover over the helicoid (3 screws) to get better access to grease the focus without taking it all apart. When you have the lens out you can unscrew the elements and then soak the aperture to remove old grease. Really very easy to work on.

Shawn

neal3k

Well-known

You can unscrew the lens and then remove the cover over the helicoid (3 screws) to get better access to grease the focus without taking it all apart. When you have the lens out you can unscrew the elements and then soak the aperture to remove old grease. Really very easy to work on.

Shawn

Thanks, that sounds within my capabilities. I'll give it a try.

farlymac

PF McFarland

My first Mercury II was kind of a basket case. What was nice though was the coverings were loose so they were very easy to remove. I then did a total tear down of the camera so I could clean up the corrosion, starting with some 400 grit paper, and working up to 3200 (conveniently sourced at an auto parts store) until I had an almost clear finish. I suppose if I'd taken some more time with it I could have gotten rid of the last of the darker spots, but I just wanted to have a clean and smooth surface. After cleaning the coverings with some Lysol, I reinstalled them using Weldbond adhesive.

The interior was a different case as the pivot point for the internal levers was worn out, and I had to resort to using thread locker to put the mounting post back in place. After that it was a matter of bending the stops back into position for proper shutter action. Then it was time to clean out the lens, and reassemble the camera.

On my second Mercury II I only had to open up the hump to gain access to the stops, again bending them back into position. That camera had not been stored in the leather case, which in a damp environment (usually a basement) is what causes the surface corrosion to occur.

They are fun cameras to use, and it's always amusing to see the looks on peoples faces.

BEFORE

Mercury II Front by P F McFarland, on Flickr

AFTER

Univex Mercury II Model CX by P F McFarland, on Flickr

PF

The interior was a different case as the pivot point for the internal levers was worn out, and I had to resort to using thread locker to put the mounting post back in place. After that it was a matter of bending the stops back into position for proper shutter action. Then it was time to clean out the lens, and reassemble the camera.

On my second Mercury II I only had to open up the hump to gain access to the stops, again bending them back into position. That camera had not been stored in the leather case, which in a damp environment (usually a basement) is what causes the surface corrosion to occur.

They are fun cameras to use, and it's always amusing to see the looks on peoples faces.

BEFORE

Mercury II Front by P F McFarland, on Flickr

AFTER

Univex Mercury II Model CX by P F McFarland, on Flickr

PF

shawn

Mentor

Mine must have been stored well as it doesn't really have any oxidation on it.

Haven't put film through it yet though. The shutter fires but I think is rotating slower than it should as it doesn't quite finish the rotation to lock the shutter closed. Not sure I'm brave enough to try tearing it down.

Shawn

Haven't put film through it yet though. The shutter fires but I think is rotating slower than it should as it doesn't quite finish the rotation to lock the shutter closed. Not sure I'm brave enough to try tearing it down.

Shawn

farlymac

PF McFarland

Mine must have been stored well as it doesn't really have any oxidation on it.

Haven't put film through it yet though. The shutter fires but I think is rotating slower than it should as it doesn't quite finish the rotation to lock the shutter closed. Not sure I'm brave enough to try tearing it down.

Shawn

Well, if you really want to know what it takes to do a total overhaul, here's how it goes https://flic.kr/s/aHsjzdMhue At least you can get an idea of how to open it up to get at different areas.

PF

Lee Rust

Member

I followed Mr. McFarland's instructions and now the Mercury is one of my favorite half-frames. Give it a try!

shawn

Mentor

Well, if you really want to know what it takes to do a total overhaul, here's how it goes https://flic.kr/s/aHsjzdMhue At least you can get an idea of how to open it up to get at different areas.

PF

Thanks, I've seen some of that before. Might try tackling it over the summer.

Thanks,

Shawn

Adapted lenses for Mercury II?

I'm looking into sourcing Mercury II lens adapters.

I'm looking into sourcing Mercury II lens adapters.

farlymac

PF McFarland

Adapted lenses for Mercury II?

I'm looking into sourcing Mercury II lens adapters.

The only one I've seen was for LTM, but it involved transplanting the optical block from the Merc lens into the adapter.

PF

The only one I've seen was for LTM, but it involved transplanting the optical block from the Merc lens into the adapter.

PF

I am looking to adapt LTM, Nikon F and OM lenses to the Mercury II -- time will tell.

farlymac

PF McFarland

I am looking to adapt LTM, Nikon F and OM lenses to the Mercury II -- time will tell.

That would be a neat trick. Would probably be a big issue on flange distance with the LTM lenses.

PF

Pál_K

Cameras. I has it.

Excellent introduction and review, Jason.

Over the years I had many opportunities to buy one of these but I ignored them due to their odd appearance. When I finally learned a bit more and then handled one, I became fascinated with it - I began to really appreciate its design.

So, finding a nice one is now on my list.

Over the years I had many opportunities to buy one of these but I ignored them due to their odd appearance. When I finally learned a bit more and then handled one, I became fascinated with it - I began to really appreciate its design.

So, finding a nice one is now on my list.

shawn

Mentor

Tested the shutter on mine and it is running very slow but each speed is pretty consistent.

1/20 = 1/6.3

1/30 = 1/7.74

1/40 = 1/8.56

1/60 = 1/12

1/100 = 1/18.8

1/200 = 1/31

1/400 = 1/54

1/000 = 1/385

The shutter speed dial looks like it isn't exactly perpendicular to the body. Think the back side might be rubbing unevenly which may be causing it to run slowly and loudly. Project for the summer but I might try putting a short roll through using the measured speeds.

Shawn

1/20 = 1/6.3

1/30 = 1/7.74

1/40 = 1/8.56

1/60 = 1/12

1/100 = 1/18.8

1/200 = 1/31

1/400 = 1/54

1/000 = 1/385

The shutter speed dial looks like it isn't exactly perpendicular to the body. Think the back side might be rubbing unevenly which may be causing it to run slowly and loudly. Project for the summer but I might try putting a short roll through using the measured speeds.

Shawn

mconnealy

Well-known

Nice to see the often-maligned Mercury being taken seriously. Would also be nice to see the quality of images it can make.

Mikut

Established

This CC-1500 Mercury has a lot of external corrosion, especially for a model CC. Internally it was in good condition with no corrosion. The shutter barely functioned and the focus was frozen. I completely overhauled the camera and it now works well. The shutter speeds are amazingly consistent. I've never encountered a shutter with this level of consistency - successive firings only vary by a fraction. Here are the results, each speed was averaged over 3 firings.

marked speed: 1/1500 tested speed: 1/2110 And no capping because there aren't 2 curtains!

1/500 1/448

1/300 1/251

1/150 1/135

1/80 1/71

1/50 1/47

1/40 1/34

The shutter has a noticeably loud slap at the end of its rotation.

I'm going to try out the camera soon but with a different lens because I've got cleaner examples. This one has some fungus and scratches.

Scott

marked speed: 1/1500 tested speed: 1/2110 And no capping because there aren't 2 curtains!

1/500 1/448

1/300 1/251

1/150 1/135

1/80 1/71

1/50 1/47

1/40 1/34

The shutter has a noticeably loud slap at the end of its rotation.

I'm going to try out the camera soon but with a different lens because I've got cleaner examples. This one has some fungus and scratches.

Scott

Share:

-

This site uses cookies to help personalise content, tailor your experience and to keep you logged in if you register.

By continuing to use this site, you are consenting to our use of cookies.